Arthur's O'on: A Scholar's Return (part 2)

This post is Part 2 of my six-part series, Arthur's O'on: A Scholar's Return, 15 Years Later. In Part 1, I introduced my first substantial research project—an MA thesis on a lost monument in Scotland—and reflected on why it mattered for my scholarly journey. If you haven't read it yet, you can start here: Arthur’s O’on: A Scholar’s Return (Part 1). Otherwise, on to Part 2...

You can now download the complete essay (all 6 parts) as a single document:

Part 2: The Monument That Was

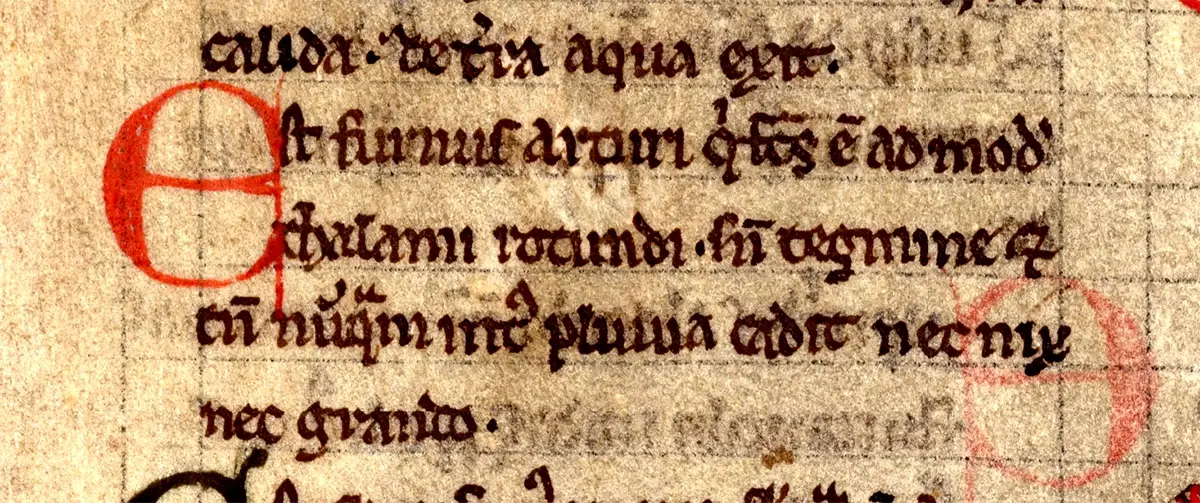

When Ralph de Diceto, dean of St. Paul's Cathedral in London, compiled his On the Wonders of Britain in the late twelfth century (CCCC MS 313, ff. 98v–100v), he listed sights that seemed both extraordinary and enduring: Cheddar Gorge, the hot springs at Bath, Stonehenge—and, nestled among them, something called furnus arturi, "Arthur's Oven." Diceto described it as "a round, roofless chamber into which rain, snow, or hail could never penetrate."

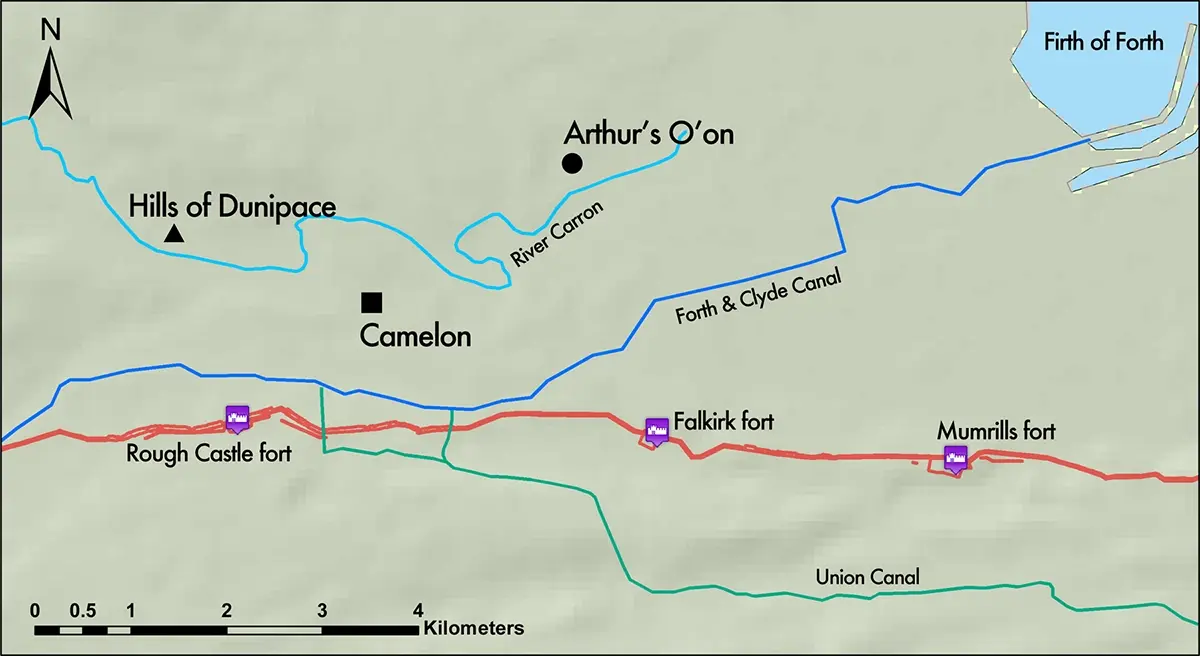

That brief sentence is one of our earliest glimpses of Arthur's O'on, the monument that once stood on the north bank of the River Carron near Falkirk. Over the centuries, this peculiar domed structure was described, debated, sketched, and even mythologized. By the early eighteenth century, it had become one of the best known "curiosities" of Roman Britain.

What it looked like

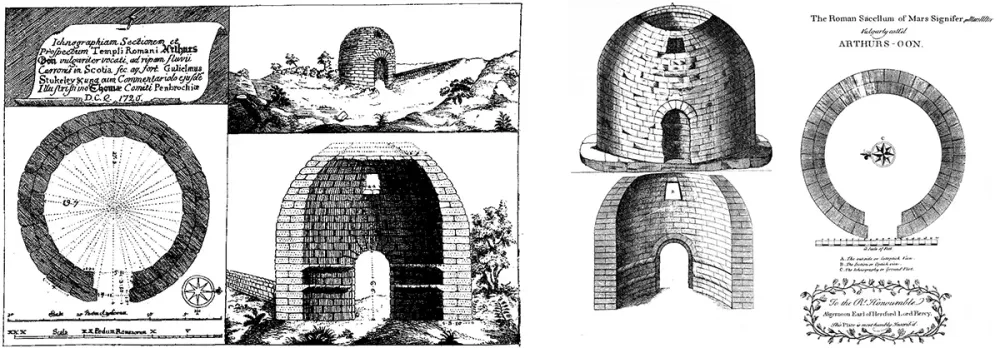

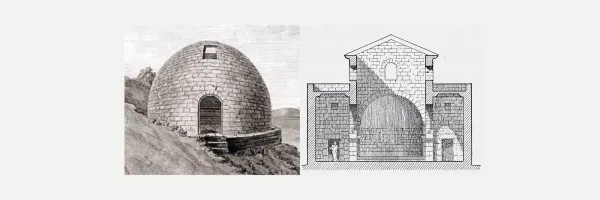

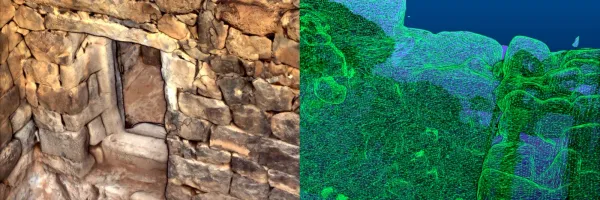

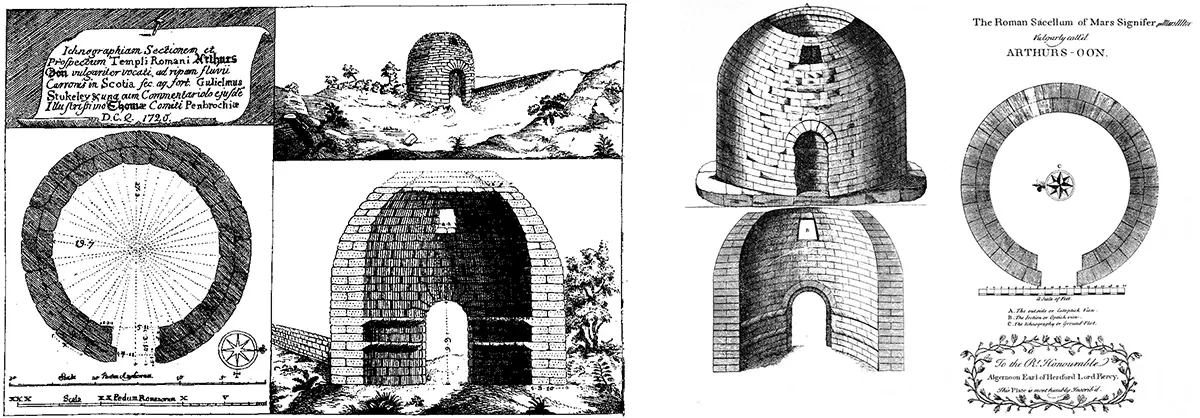

Thanks to detailed antiquarian descriptions and drawings by William Stukeley (1720), Alexander Gordon (1726), and others, we can reconstruct the O'on's appearance with some confidence. It was a circular ashlar masonry building, about 22 feet tall, with an internal diameter just under 20 feet. The walls were built of finely dressed stone in corbelled courses—at least 23 layers in all—without visible mortar.

The doorway, more than nine feet high, faced east, and directly above it was a trapezoidal window, aligned with an open aperture at the very top of the dome. Inside, the floor was paved, with a large stone in the center that may have been an altar or base for a statue. Some antiquarians (e.g., Sir Robert Sibbald) even reported carvings of eagles, winged victories, or military symbols. The combination of fine stonework, symbolic decoration, and monumental scale made it unlike anything else in Britain.

In short: it was striking, unusual, and, for many, unforgettable. No wonder John Clerk of Penicuik, writing in 1743 after the O'on's destruction, could call it "the best and most entire old building in Britain."

A Wonder of Britain

From the twelfth century onward, Arthur's O'on circulated in both learned and popular traditions. Medieval chroniclers linked it to King Arthur. Early modern writers claimed it was a victory monument left by Julius Caesar, or a temple of the god Terminus, or a shrine to Mars Ultor. By the time of Stukeley and Gordon, the Roman attribution had become mainstream, and both men believed it was a Romano-British temple, tomb, or trophy associated with the Antonine Wall (which hadn't yet received that name or been correctly identified with its commissioning emperor Antoninus Pius, but that's a different story—one I covered in my subsequent doctoral research—that I'll tell here sometime soon!). Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, Midlothian, used Gordon's plans and measurements to reconstruct a replica atop the stable-blocks at Penicuik House, functioning as a dovecote.

In truth, we cannot be certain what its original purpose was. Modern consensus, following Kenneth Steer's mid-twentieth-century study, identifies it as a tropaeum—a Roman victory monument—probably dating to the Antonine period (c. 140–160 CE). But what mattered more than its precise function was the awe it inspired. For Stukeley, it was "the most genuine and curious Antiquity of the Romans in this Kind, now to be seen in our Island or elsewhere."

My first deep dive into antiquarian sources

As a young MA student, piecing this story together meant immersing myself in medieval and early modern manuscripts, printed tracts, and eighteenth-century correspondence. It was the first time I had to do the painstaking work of comparing conflicting descriptions, deciphering paleographic "hands" of different periods—and the peculiarities of medieval and early modern Latin, English, and Scots writing—weighing drawings against measurements, and trying to imagine what no longer stood from the evidence left behind by such disparate records.

I remember feeling both the thrill and the frustration of absence: the O'on itself was gone, yet the documentary trail was dense. It forced me to think critically about sources, interpretation, and the "archaeology of knowledge" long before I had the vocabulary to express those ideas with confidence.

In retrospect, this was my first encounter with what I would later call the "archaeology of place." Arthur's O'on was not just a building or an artifact from one particular period and with one particular function: it was a place in the landscape, layered with memories and meanings that shifted with each new description, drawing, or myth. That realization shaped much of my later scholarship, and it began right here, in the shadows of a lost stone dome on the Carron.

What comes next

Of course, the story of Arthur's O'on is not only about what it looked like, what period it was built in, its functional purpose, or how it was described. It is also about what happened to it—the antiquarian debates, the folklore it generated, and ultimately, its destruction in the 1740s.

In the next part of this series, I will turn to those myths, names, and contested interpretations: how Arthur's O'on became Camelot for some, Caesar's sleeping chamber for others, and why stories can be just as enduring as stone.

Continue reading this series:

- Part 1: Looking Back, Looking Forward

- Part 2: The Monument That Was (current page)

- Part 3: Myths, Names, and the Making of Meaning

- Part 4: Destruction and Outrage

- Part 5: Afterlives and Reimaginings

- Part 6: Fifteen Years On—Fom Falkirk to Jordan

Or download the complete essay (all 6 parts) as a single document: