Arthur's O'on: A Scholar's Return (part 3)

This is Part 3 of my six-part series, Arthur's O'on: A Scholar's Return, 15 Years Later. In Part 1, I looked back at my 2009 MA thesis and how it shaped my path as a scholar, setting the mission for this series. Part 2 reconstructed what Arthur's O'on looked like, how we know, and why antiquarians considered it a wonder of Roman Britain. Here, I turn to the myths, names, and stories that gave the monument layers of meaning long after its stones were set in place.

You can now download the complete essay (all 6 parts) as a single document:

Part 3: Myths, Names, and the Making of Meaning

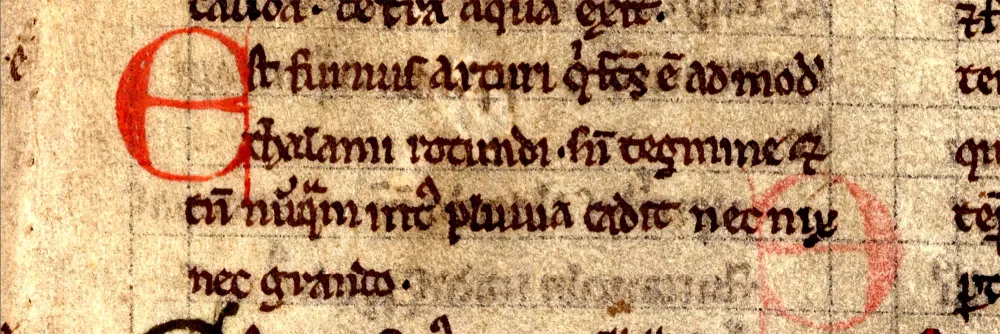

By the time medieval chroniclers began to write about the stone dome on the River Carron, its Roman origins were already fading from memory. In John of Fordun's fourteenth-century Chronica Gentis Scotorum, the building appears as a rotundam casulam columbaris ad instar—"a round chamber, in the form of a dovecote." He gives his own theory that this structure was built by Julius Caesar who had built it as as a boundary marker or "lasting monument" at the northern edge of his campaigns in Britain, but also reports another story—"chiefly a rumour spreading among the multitude"—that the structure was a kind of movable "stone tent" that was rebuilt daily so that Caesar could rest more safely than canvas would allow, and that it had been left behind only because of an urgent need to return to the continent.

This was the beginning of a long tradition of making meaning around Arthur's O'on. Lacking direct knowledge of its purpose, writers and local communities filled the gap with their own stories.

Arthur's Oven, Camelon, Camelot

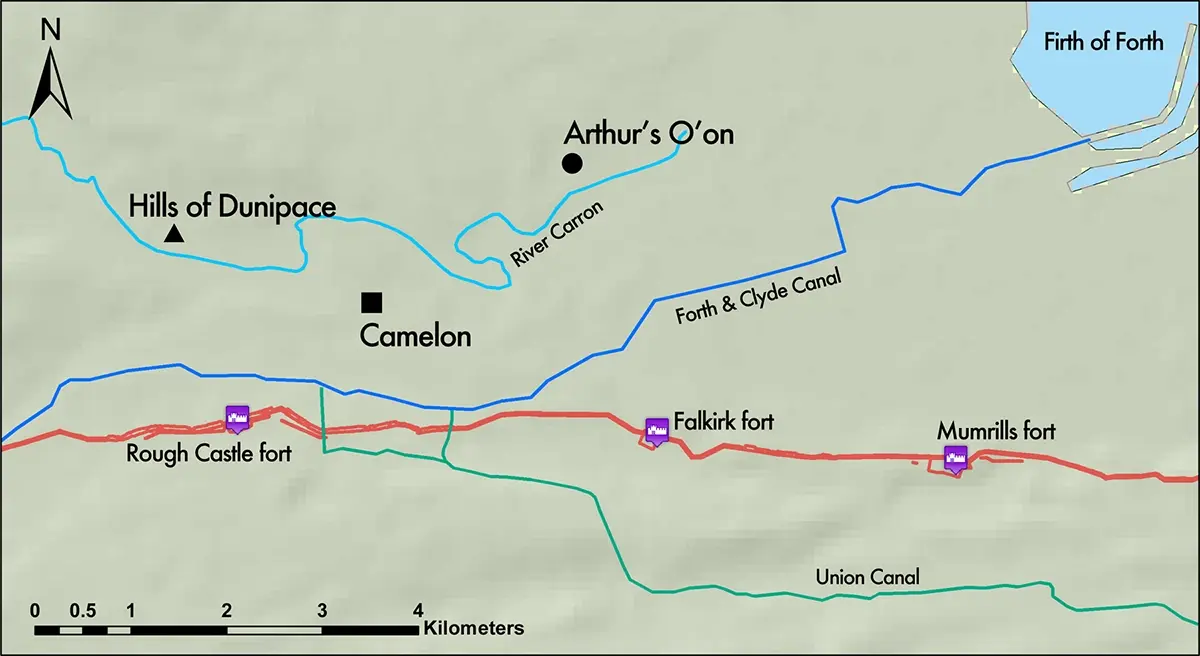

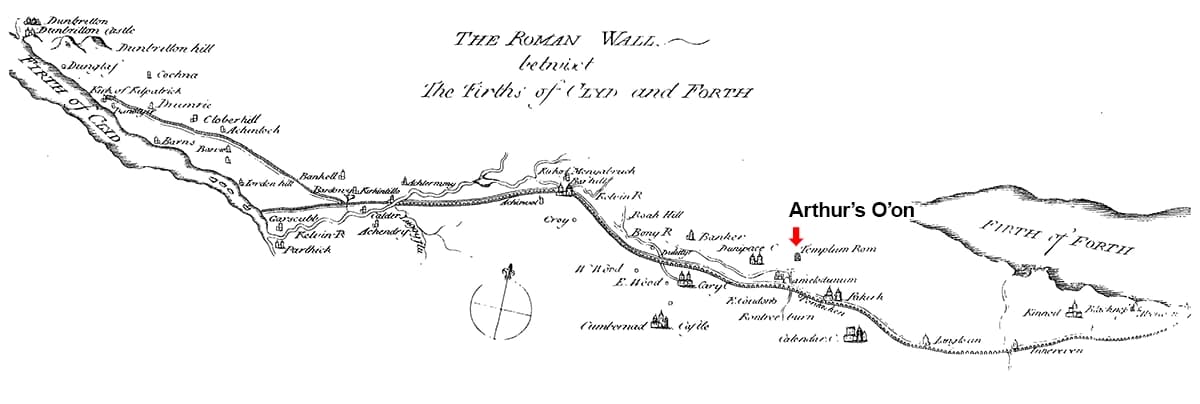

By the late Middle Ages, the monument's popular name was "Arthur's Oven" (Arthur's O'on in Scots). The reasons are not entirely clear, but proximity to the village of Camelon (pronounced "came-lon") may have invited associations with Arthurian legend. Some identified Camelon with Camelot itself. In this mythic landscape, the domed structure became a fitting relic of Britain's heroic age: a place where Arthur might once have feasted, fought, or worshiped.

The O'on thus entered folklore as one of Britain's wonders. The name survived even into modern place-names: Stenhousemuir, the town that grew nearby, takes its identity from the "stone house" (i.e., Arthur's O'on) that no longer stands there.

Antiquarian imaginations

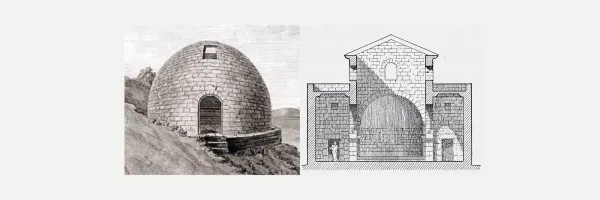

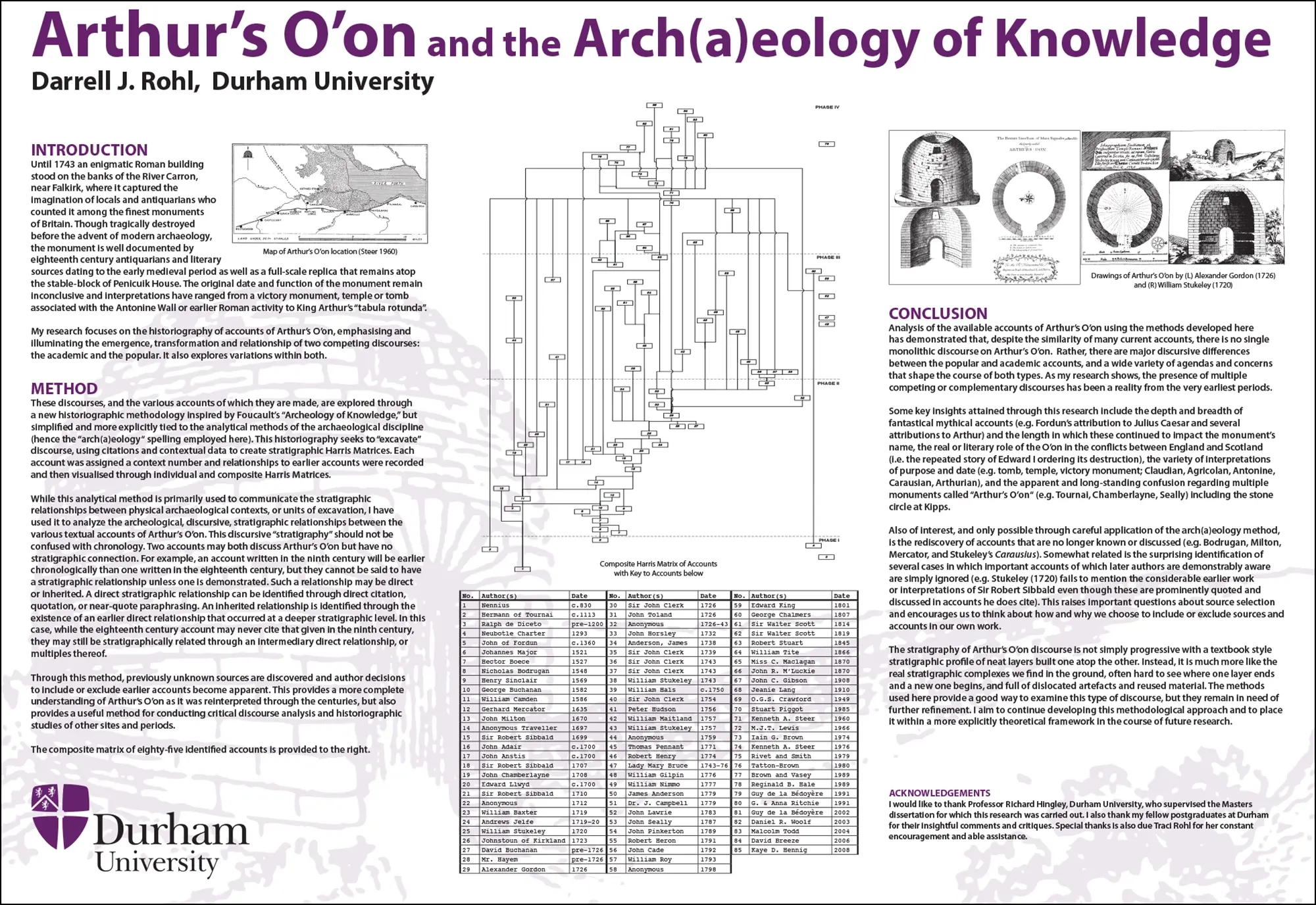

Eighteenth-century antiquaries, meanwhile, were busy debating the O'on’s origins. William Stukeley, never one to understate, proclaimed it a Roman temple dedicated to Romulus, the city's founder and "primitive Deity of the Romans." Without ever having visited Scotland—but having commissioned the architect Andrews Jelfe to survey and report on the monument for him—he compared it to the Pantheon in Rome. The scotsman Alexander Gordon, who had seen it shortly after Stukeley's publication, insisted instead that it was a shrine for the Roman military standards.

Each interpretation was as much about the antiquary's own imagination as about the building itself. Stukeley's romantic comparanda, Gordon's military focus, Fordun's Julius Caesar, the medieval Camelot associations—all reveal more about the tellers than about the monument.

Meaning as much as masonry

What fascinates me, looking back, is how Arthur's O'on became a vessel for so many different narratives: Roman trophy, Arthurian relic, dovecote, temple, shrine, wonder. Each generation projected its own values and questions onto the silent stones.

This is exactly what I would later come to frame as the archaeology of place: the recognition that monuments are never fixed in meaning. They are reinterpreted and reimagined, and those re-imaginings shape identities and landscapes just as surely as walls and domes.

As a young researcher, I could see that Arthur's O'on was more than just an archaeological puzzle. It was a case study in how communities—medieval, early modern, antiquarian, contemporary—construct the past to make sense of their own present. I didn't yet have the language of "chorography" at my disposal, but the seeds were here.

What comes next

Of course, these stories and meanings make the O'on's fate all the more poignant. In Part 4, I'll turn to the eighteenth-century scandal of its destruction: how Sir Michael Bruce tore it down for dam stones, how antiquaries across Britain fumed in outrage, and what that tells us about the values attached to monuments—and the consequences when those values are ignored.

Continue reading this series:

- Part 1: Looking Back, Looking Forward

- Part 2: The Monument That Was

- Part 3: Myths, Names, and the Making of Meaning (current page)

- Part 4: Destruction and Outrage

- Part 5: Afterlives and Reimaginings

- Part 6: Fifteen Years On—Fom Falkirk to Jordan

Or download the complete essay (all 6 parts) as a single document: