Arthur's O'on: A Scholar's Return (part 4)

This is Part 4 of my six-part series, Arthur's O'on: A Scholar's Return, 15 Years Later. In Part 1, I looked back at my 2009 MA thesis and how it set me on the path toward chorography and the archaeology of place. Part 2 reconstructed the lost monument itself and how eighteenth-century antiquaries played a crucial role in documenting it, while Part 3 explored the many myths and meanings that people attached to it over time. Here, I turn to later in the eighteenth century, when Arthur's O'on met its tragic end—and when antiquaries across Britain raised their voices in outrage.

You can now download the complete essay (all 6 parts) as a single document:

Part 4: Destruction and Outrage

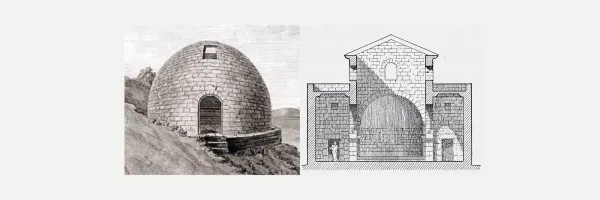

By the early eighteenth century, Arthur's O'on was one of the most celebrated antiquities in Scotland—indeed, in all of Britain. Antiquarians described it in glowing terms, artists sketched it, and scholars debated its origins. For William Stukeley, it was "the most genuine and curious Antiquity of the Romans in this Kind, now to be seen in our Island or elsewhere."

And then, in 1743, it was gone.

The demolition

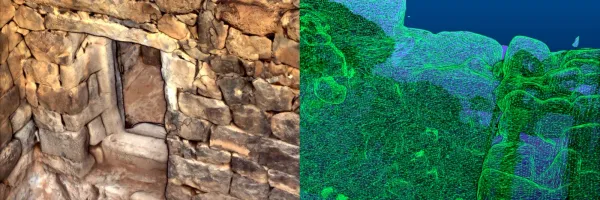

Sir Michael Bruce of Stenhouse, whose estate straddled the River Carron, had decided that his new mill needed a dam. Rather than quarry fresh stone, he turned to the ancient structure standing nearby. Arthur's O'on, with its carefully dressed ashlar blocks, was in his eyes a ready-made source of high-quality building material.

Within weeks, the best-preserved Roman monument in Scotland was reduced to nothing, its stones—even the foundations—pried apart and carried away for the dam's construction.

For Bruce, this was pragmatic economics. For antiquaries, it was cultural vandalism of the highest order. The irony was cruel: a building that had survived nearly sixteen centuries of weather, warfare, and neglect was undone by the spade of its landlord.

Antiquarian outrage

The reaction was swift and furious. Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, a leading Scottish antiquary, called it the work of a "Goth," lamenting that "no other motive had this Gothic knight, but to procure as many stones as he could have purchased in his own quarries for five shillings." His friend Roger Gale transcribed the news into the minutes of the Society of Antiquaries of London, ensuring that the demolition would be remembered as a cautionary tale of wanton destruction.

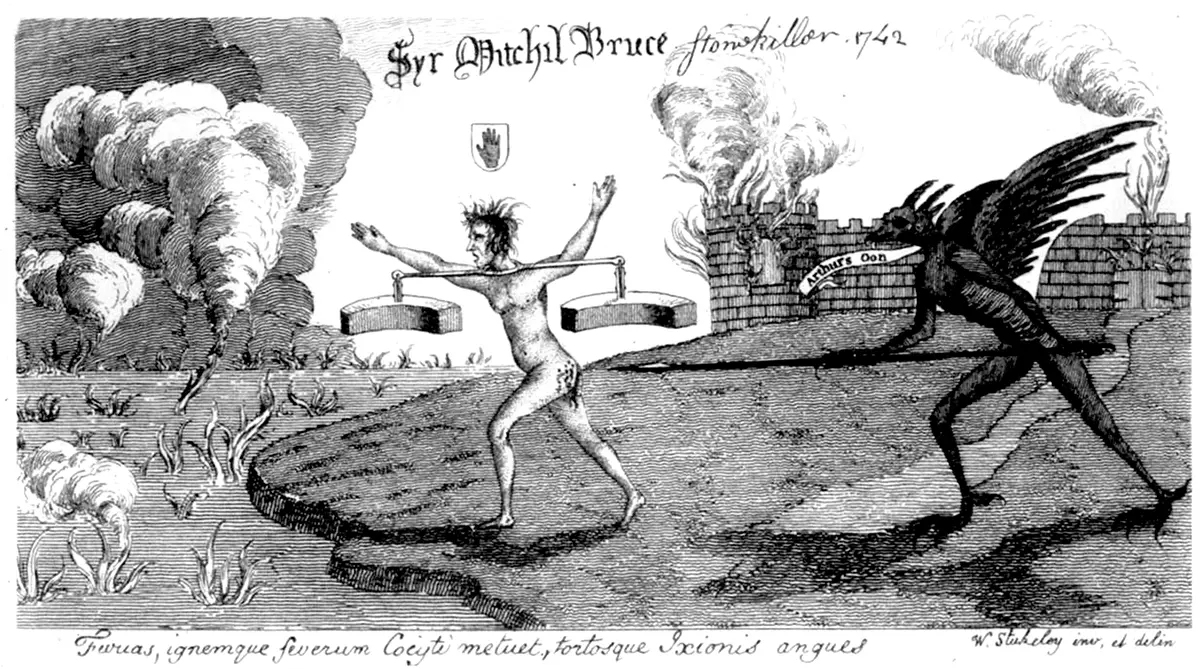

William Stukeley, who had never seen the O'on in person but had increased its famous through his engravings and published tract, was enraged. In one extraordinary drawing, he imagined Bruce suffering divine and eternal punishment. For Stukeley, Bruce's crime was not only against Scotland, but against Rome itself, whose noble legacy had been desecrated. In a letter he sent to Gale with the image, he says that:

I would propose, in order to make his name execrable to all posterity, that he should have an iron collar put about his neck, like a yoke; at each extremity a stone of Arthur's O'on to be suspended by the lewis in the hole of them; thus accoutred, let him wander on the banks of Styx, perpetually agitated by angry demons with oxgoads; "Sir Michael Bruce," wrote on his back in large letters of burning phosphorus.

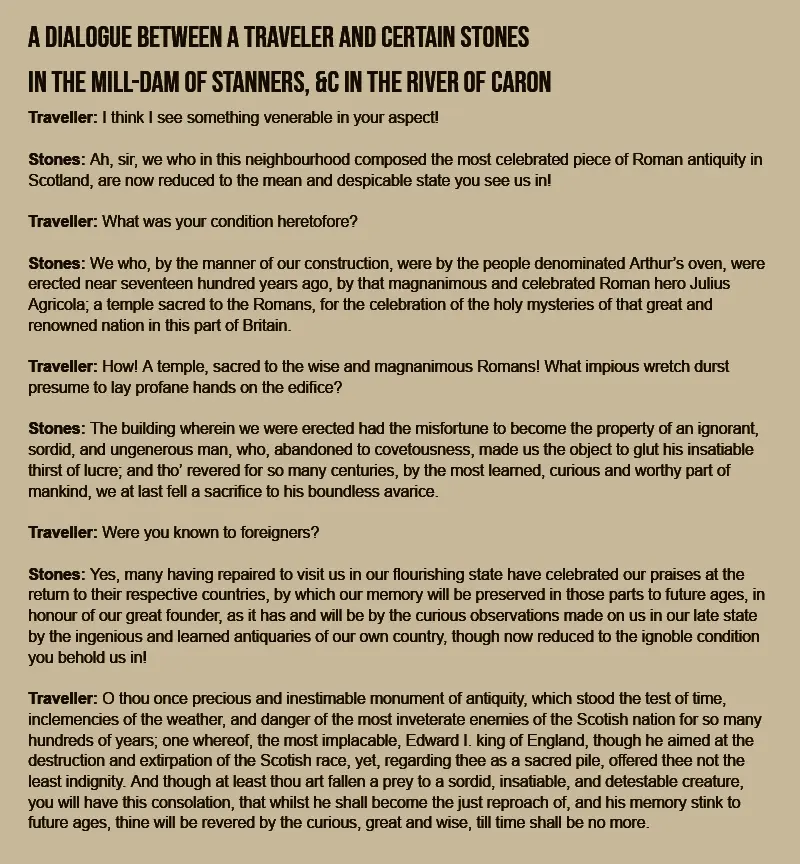

The outrage also spilled into verse. One poet imagined a traveler walking along the Carron, conversing with the scattered stones of the demolished O'on. Each fragment laments its fate, recalling the monument's former glory and cursing the man who destroyed it. The pathos is striking: the monument itself, through its fragments, becomes a witness to its own undoing.

In another letter to Gale, Clerk condemned Bruce "with Bell, Book, and Candle," calling down ecclesiastical malediction upon his name. Five years later, while still fulminating in letters, Clerk gleefully reported that the mill and dam built from the O'on's stones had been destroyed by thunder and lightning. For him and others, this was poetic justice: nature herself had avenged the ruin of Arthur's O'on.

But Clerk's response went beyond fury. At his estate of Penicuik House, he instructed his son James to design a new stable block crowned by a dome modeled directly on Arthur's O'on. Using Alexander Gordon's drawings and descriptions as a guide, they built a dovecote replica perched above the stables. It still stands today. Outrage had given birth to reconstruction: the O'on was gone from the Carron, but reborn in stone on the slopes of Penicuik.

Sacrificed to the Industrial Age

To modern minds, the O'on's destruction seems almost symbolic: a sacrifice to the onrushing industrial age. Only a few years later, the Carron Ironworks would rise nearby, producing cannon for Britain's wars and growing into one of Europe's largest industrial plants. The Carron, once a river of Ossianic legend and Roman frontiers, had become a corridor of mills, forges, and smoke.

Arthur's O'on thus became an early casualty of industrial progress, reduced to fuel the very transformation that would dominate the modern world. Yet the fury it provoked is telling. Antiquaries did not shrug off its loss: they mourned, cursed, mythologized, and sought to preserve its memory in word, image, and stone. Their outrage demonstrates that even in the eighteenth century, heritage mattered—not only the survival of stone, but the survival of meaning, identity, and wonder.

Reflections on destruction

As an MA student reading these letters and reports, I was struck by how alive the emotions were. Clerk's indignation, Gale's despair, Stukeley's lament—they were reminders that monuments are not inert. They matter, and when they are destroyed, people feel that loss viscerally.

Today, when we witness the deliberate destruction of monuments in war zones, or the steady erosion of heritage under development pressure, the debates feel uncannily familiar. The questions raised in 1743—what value do we place on the past, who gets to decide its fate, and how should we respond to its loss—remain urgent today.

What comes next

But even in absence, Arthur's O'on endured. It was rebuilt, reimagined, and remembered in unexpected ways: as a dovecote replica at Penicuik House, in Ossianic verse, in nineteenth-century romantic antiquarianism, and even in a twenty-first-century book by Charlotte Higgins. In Part 5, I'll turn to these afterlives—how a demolished monument refused to vanish from cultural memory.

Continue reading this series:

- Part 1: Looking Back, Looking Forward

- Part 2: The Monument That Was

- Part 3: Myths, Names, and the Making of Meaning

- Part 4: Destruction and Outrage (current page)

- Part 5: Afterlives and Reimaginings

- Part 6: Fifteen Years On—Fom Falkirk to Jordan

Or download the complete essay (all 6 parts) as a single document: