Arthur's O'on: A Scholar's Return (part 5)

This is Part 5 of my six-part series, Arthur's O'on: A Scholar's Return, 15 Years Later. In Part 1, I looked back at my 2009 MA thesis and how it set me on the path toward chorography and the archaeology of place. Part 2 reconstructed the lost monument itself, while Part 3 explored the many myths and meanings that people attached to it. Part 4 turned to the eighteenth century and the scandal of its destruction. Here, I explore how Arthur's O'on lived on in memory, literature, replicas, and cultural imagination.

You can now download the complete essay (all 6 parts) as a single document:

Part 5: Afterlives and Reimaginings

When the last stones of Arthur's O'on were carted away for Sir Michael Bruce's mill dam in 1743, antiquaries declared the monument "lost." And yet, in a very real sense, it never disappeared. Over the next centuries, the O'on was reborn in memory, rebuilt in replica, and reimagined in stories.

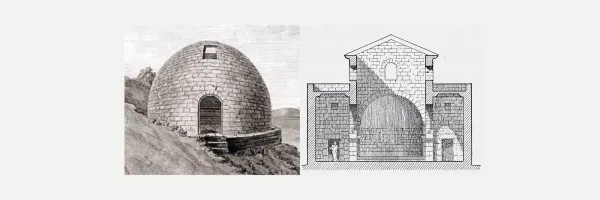

The Penicuik replica

The most tangible afterlife of Arthur's O'on stands today in Midlothian. Sir James Clerk, son of the furious antiquary Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, built a new Arthur’s O'on atop the stables at Penicuik House in the 1760s. This replica was intended as a dovecote, and its domed roof still rises above the estate. Antiquarians at the time praised it as an act of preservation: if the original could not be saved, at least its form would live on.

To modern visitors, the Penicuik replica raises questions about authenticity. Is a copy "real"? Does rebuilding preserve memory, or obscure it? These are not antiquarian questions alone. They echo in debates over heritage reconstruction today, from Warsaw's Old Town to Palmyra's temples and arches.

Romantic ruins and Ossianic landscapes

The O'on also lived on in literature. James Macpherson's Poems of Ossian (1760s) presented themselves as translations of ancient Gaelic epics handed down from the third-century bard Ossian. To many contemporaries, they seemed like a Scottish Homer, proof that Scotland's landscape was alive with echoes of heroic antiquity.

Almost immediately, critics accused Macpherson of fraud. Samuel Johnson dismissed the poems as "forgeries," while others questioned his sources and methods. Debate has never fully subsided: were the Ossianic poems authentic survivals of ancient tradition, or largely Macpherson's invention? Most scholars today acknowledge both—the poems were stitched together from fragments of genuine oral tradition, but heavily reworked, expanded, and framed by Macpherson's own romantic sensibilities and new knowledge of the past revealed in recent decades by the work of antiquarians like Sibbald, Gordon, and Stukeley.

Yet whether ancient epic or eighteenth-century creation, Ossian mattered. The poems inspired Goethe and Napoleon, captivated Romantic artists, and reshaped how Scotland's landscapes were imagined. They also provided a vivid literary afterlife for Arthur's O'on.

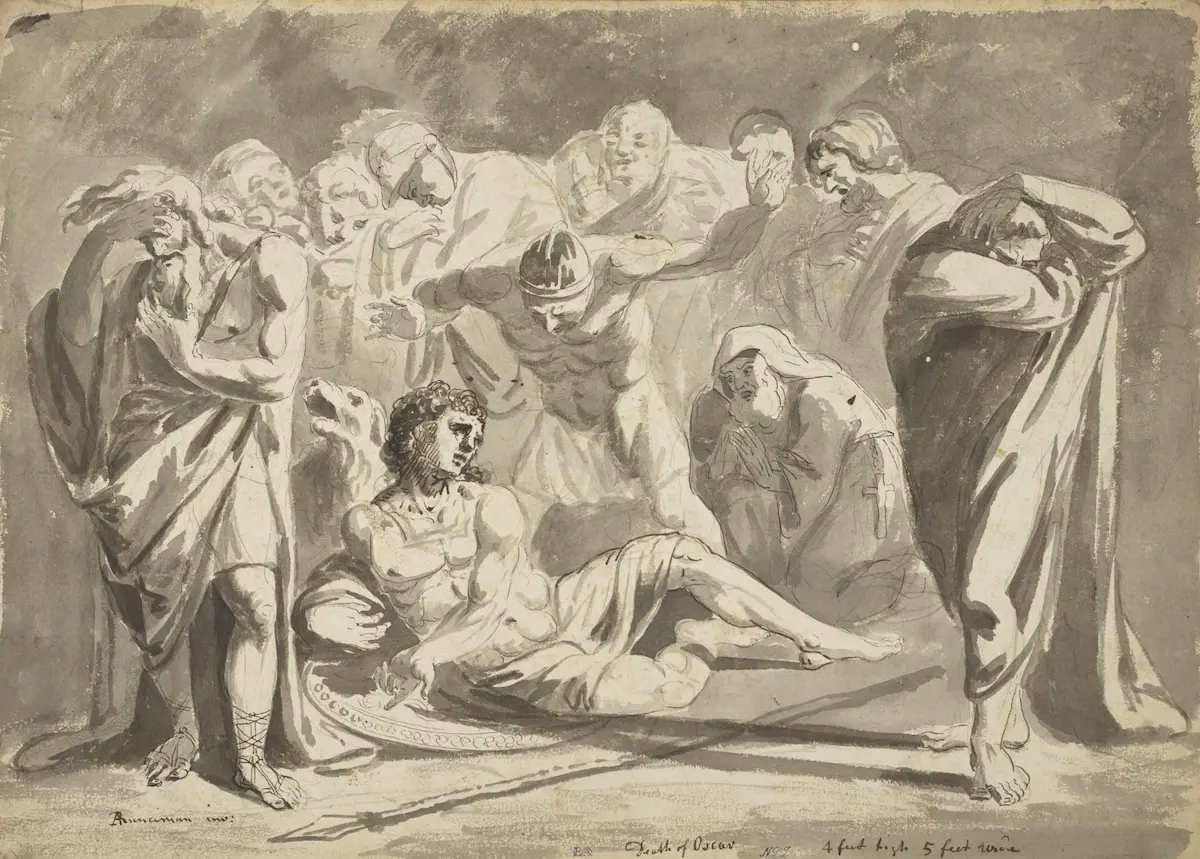

Two poems in particular are relevant. In Comála: A Dramatic Poem, the River Carron runs red with blood as a young woman laments her beloved Fingal, thought dead in battle. The setting on the Carron—where Arthur's O'on once stood—becomes a stage for tragedy and love lost. In The War of Caros, the poet's son Oscar—grandson of Fingal—fights the Roman usurper Carausius on the same banks, his heroism immortalized against the backdrop of tumuli and ruins. Both poems tie memory, loss, and landscape into a single dramatic vision.

Quotations capture the tone and also the geography:

O Carun of the streams! why do I behold thy waters rolling in blood? (Comála: A Dramatic Poem)

What does Caros king of ships, said the son of the now mournful Ossian? spreads he the wings of his pride, bard of the times of old?

He spreads them, Oscar, replied the bard, but it is behind his gathered heap. He looks over his stones with fear, and beholds thee terrible, as the ghost of night that rolls the wave to his ships. (The War of Caros)

Later in the same poem, after days of battle, Oscar is alone "on the banks of Carun:"

A green vale surrounded a tomb which arose in the times of old. Little hills lift their head at a distance; and stretch their old trees to the wind. The warriors of Caros sat there, for they had passed the stream by night. They appeared, like the trunks of aged pines, to the pale light of the morning.

Oscar stood at the tomb, and raised thrice his terrible voice. The rocking hills echoed around: the starting roes bounded away. And the trembling ghosts of the dead fled, shrieking on their clouds. So terrible was the voice of my son, when he called his friends. (The War of Caros)

The imagery here is striking. The "heap" behind which Caros (the usurper Carausius) and his men are said to cower is almost certainly the Antonine Wall itself—the massive turf rampart and ditch cutting across central Scotland just south of the Carron. And the "tomb" in the "green vale," before which Oscar raises his cry, is best read as Arthur's O'on. For eighteenth-century readers familiar with the monument and its landscape, these references would have been unmistakable: the lost dome of the O'on transformed into the resting place of Caledonian heroes, standing in poetic counterpoint to Rome's northernmost frontier.

This is precisely how Macpherson's Ossian worked: weaving landscape, ruin, and legend together in ways that collapsed time and gave stones new voices. Even if the poems were largely his invention, they exemplify the enduring power of heritage storytelling. Arthur's O'on became not just an antiquarian curiosity but a stage for epic battles, laments, and heroic memory.

The Penicuik replica and the "Hall of Ossian"

The Clerk family's replica of Arthur's O'on at Penicuik House formed part of the same cultural moment. It was not built in isolation, but within a broader landscape of memory and imagination. Inside Penicuik House, Sir James Clerk designated one room as the "Hall of Ossian," commissioning the artist Alexander Runciman to paint the walls and ceilings with scenes from Ossian's poems. Outside, the dovecote replica of Arthur's O'on anchored the estate in Roman and antiquarian history. Together, they created a paired celebration of Scotland's actual and mythic pasts: Ossian's literary ruins on the walls and ceilings, Arthur's O'on resurrected in stone above the stables.

This blending of antiquarian reconstruction and literary imagination speaks volumes about eighteenth-century heritage-making. For the Clerks and their circle, history was not just about facts. It was about evocation, imagination, and giving physical form to memory. The O'on, Ossian, and Penicuik together formed a dialogue between invention and authenticity that still resonates in heritage debates today.

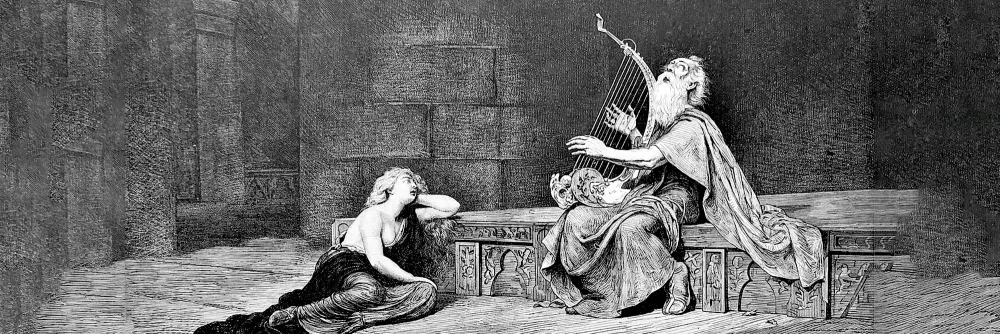

While the replica of Arthur's O'on remains today, Penicuik's "Hall of Ossian" was destroyed by fire in 1899. The original paintings are, therefore, lost forever but some of Runciman's preliminary sketches are preserved in the National Galleries of Scotland.

Twentieth and twenty-first century memory

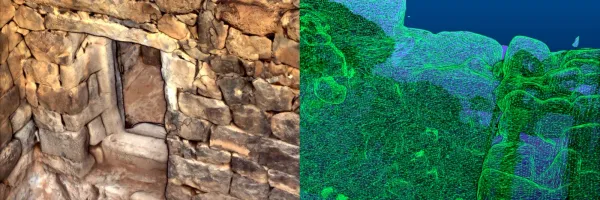

Though neglected by professional archaeologists—with the notable exception of Ken Steer—for much of the twentieth century, Arthur's O'on never fully left the stage. It cropped up in local heritage societies, in guidebooks to the Antonine Wall, and in the footnotes of Roman Scotland studies.

In 2013, journalist Charlotte Higgins revived the story for a new audience. Her book Under Another Sky: Journeys in Roman Britain—shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize and other non-fiction book awards—devoted a chapter to Roman Scotland, including Arthur's O'on, weaving elements of my own MA and PhD research into her narrative.

Meaning in absence

For me, these afterlives are as significant as the monument itself. They show that heritage does not end when stones are toppled. Arthur's O'on survived because people remembered it, talked about it, rebuilt it, and reimagined it. In its absence, it became more pliable—able to serve as a romantic ruin, a local legend, a scholarly case study, even a symbol of loss.

This realization was one of the seeds of my own later work: to study not just monuments as they were built, but as they are remembered, retold, reimagined, and repurposed. In that sense, the O'on has never stopped teaching me.

What comes next

In the final part of this series, I will step back and reflect more personally: what Arthur's O'on has meant to me as a scholar, how it influenced my turn to chorography and the archaeology of place, and why a lost monument in Scotland still shapes the way I work in Jordan today.

Continue reading this series:

- Part 1: Looking Back, Looking Forward

- Part 2: The Monument That Was

- Part 3: Myths, Names, and the Making of Meaning

- Part 4: Destruction and Outrage

- Part 5: Afterlives and Reimaginings (current page)

- Part 6: Fifteen Years On—Fom Falkirk to Jordan

Or download the complete essay (all 6 parts) as a single document: