Arthur's O'on: A Scholar's Return (part 6)

This is the final part of my six-part series, Arthur's O'on: A Scholar's Return, 15 Years Later. Part 1 looked back at my 2009 MA thesis and how it set me on the path toward chorography and the archaeology of place. Parts 2–5 explored the monument itself (Part 2) its myths and meanings (Part 3), the scandal of its destruction (Part 4), and its afterlives in replicas, literature, and memory (Part 5). Here, I step back for a broader reflection: how this early research shaped my scholarly journey, and how its themes continue to echo in my work today at Umm Al-Jimal in Jordan.

You can now download the complete essay (all 6 parts) as a single document:

Part 6: Echoes Across Ruins—From Arthur's O'on to Umm Al-Jimal

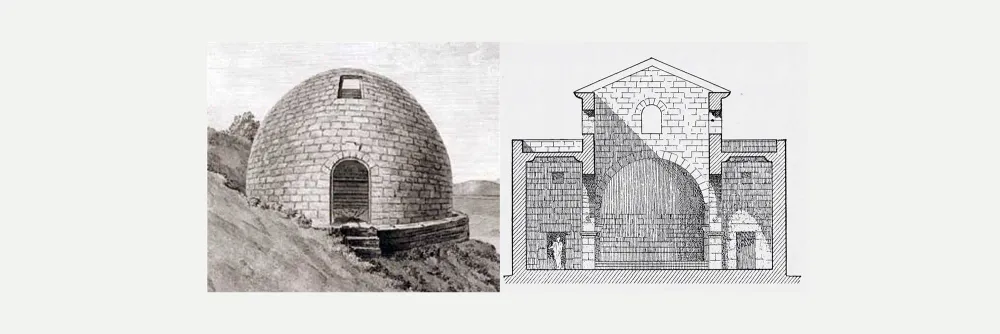

A little more than fifteen years ago, I chose to study a monument that no longer existed. Arthur's O'on was demolished in the 1740s, its stones carted off for a mill dam, its memory preserved only in antiquarian drawings, letters, poems, and folklore. My task was to reconstruct not just its appearance and possible function (for the record, I think a tomb interpretation is most likely), but its story: how people imagined it, named it, fought over it, and mourned its loss.

At the time, I knew I was tackling a niche subject. What I didn't yet realize was that Arthur's O'on was teaching me something much bigger. It showed me that archaeology is never just about stones and the stuff we uncover. It is also about stories. Sites and monuments matter not only for what they were in the past, but for how they are remembered, retold, and reimagined.

This realization became the seed of my later work on chorography—the study of place as layered with history, meaning, and imagination—and the archaeology of place, an approach that continues to guide my research today. I didn't discover chorography on my own, but was guided to it by my MA/PhD supervisor Prof. Richard Hingley, and I'm grateful to him for steering me in this direction.

Echoes at Umm Al-Jimal

Years later, when I began working at Umm Al-Jimal in northern Jordan, I encountered the same dynamic in a different landscape. Umm Al-Jimal is a sprawling site of basalt ruins, with houses, churches, water reservoirs, two Roman forts, and the ruins of multi-storey buildings in the desert. While incredibly different in terms of form and scale, like Arthur's O'on, it invited both careful evidence-based inquiry and fascination and creative invention.

Nineteenth-century travelers recorded a wealth of local stories about the site. John Burckhardt heard that its name meant "Mother of Camels" and linked it to caravans resting there. Selah Merrill collected tales of buried treasure. Cyril Graham reported ghostly figures seen among the ruins at night. And the American missionary William Ewing wrote down a particularly vivid legend: that the Prophet Mohammed (peace be upon him) had hidden vast treasure beneath Umm Al-Jimal, "guarded by forty giant negroes, an enormous camel, and a snake whose vast sinewy folds remind one of Leviathan."

These stories were not "accurate" in a historical sense, just as Arthurian legends or Caesar's "stone tent" were not accurate accounts of Arthur's O'on. But they were powerful. They explained the ruins to those who lived alongside them. They invested the stones with meaning, whether sacred, dangerous, or enchanted.

In Scotland, Arthur's O'on became associated with Arthurian Camelot, Caesar's trophy, or a temple of Mars. In Jordan, Umm Al-Jimal became the site of hidden treasure, supernatural guardians, or petrified people. In both cases, ruins inspired stories, and those stories gave the ruins new life.

Lessons for heritage and scholarship

For me, the continuity is striking. My MA thesis on Arthur's O'on taught me to listen not just to archaeology, but to the voices surrounding archaeology: the folklore, the myths, the antiquarian passions, the literary retellings. Umm Al-Jimal confirmed that this listening is not optional: it is essential. If we want to understand how heritage works in human societies, we must pay attention to how people imagine, narrate, and even mythologize ruins.

This perspective has carried me from Scotland to Jordan, from a demolished dome on the River Carron to the basalt homes and towers of Umm Al-Jimal, from a student project to a career in archaeological research and world heritage work. It has shaped how I think about digital tools and methods for heritage, UNESCO nominations, and the responsibilities of archaeologists to living communities.

A personal reflection

Looking back, I can now see that Arthur's O'on was never just a quirky antiquarian puzzle. It was my training ground. It taught me how to read ruins as texts, how to see landscapes as layered narratives, and how to understand that loss itself can generate meaning.

And as I walk through Umm Al-Jimal today—past churches now roofless, towers crumbling, stones covered in lichen from centuries of abandonment—I hear the echoes of Arthur's O'on. I hear them in the treasure tales, the ghost stories, the local names, and in the urgent questions about how to preserve and present this heritage for the future. And when we encounter signs of looting or vandalism, I feel the righteous anger expressed centuries ago by Clerk and Stukeley.

Arthur's O'on is gone. Umm Al-Jimal still stands. But both remind me of the same truth: that ruins endure not only in stone, but also in story. In the face of continued threats to the "wonders" left over from the past, that, perhaps, is the most powerful lesson archaeology has to offer.