Umm Al-Jimal: Adventurers, Antiquarians, and Arabian Nights

This is Part 2 of a 3-part series of posts introducing the site of Umm Al-Jimal, Jordan, the current focus of my work as a scholar of archaeology and heritage. In the first part of this series, we explored Umm Al-Jimal's remarkable preservation, its name and setting, and the story of how this black-basalt town in northern Jordan became a World Heritage Site. Now we turn back to the nineteenth century, when early explorers and travelers—drawn by rumor, rivalry, and romance—first brought the site to Western attention. Their encounters, quarrels, and imaginings would shape how the "Mother of Beauty"/ "Mother of Camels" was seen for generations.

Continue reading here, or download the complete essay (all 3 parts) as a single document:

Part 2: Adventurers, Antiquarians, and Arabian Nights

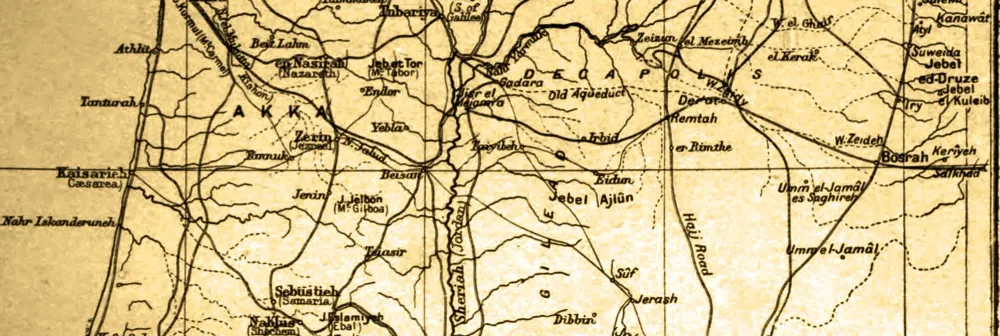

On Jordan's northeastern plain, Umm Al-Jimal rises like a black city of stone. For centuries, its towers and courtyards stood quietly among the basalt fields, known to shepherds and Bedouin but largely invisible to the outside world. That began to change in the early nineteenth century, when European travelers—hungry for biblical discoveries, ancient ruins, and adventure—set their sights on the Hauran.

The result was not a neat line of rediscovery but a tangle of missed attempts, rivalries, lawsuits, and legends. Before archaeologists arrived with cameras and measuring tapes, Umm Al-Jimal lived in the Western imagination as an enchanted city, a bandit's fortress, or even a cavern of treasure guarded by serpents and giant figures.

Burckhardt: The Explorer Who Missed It

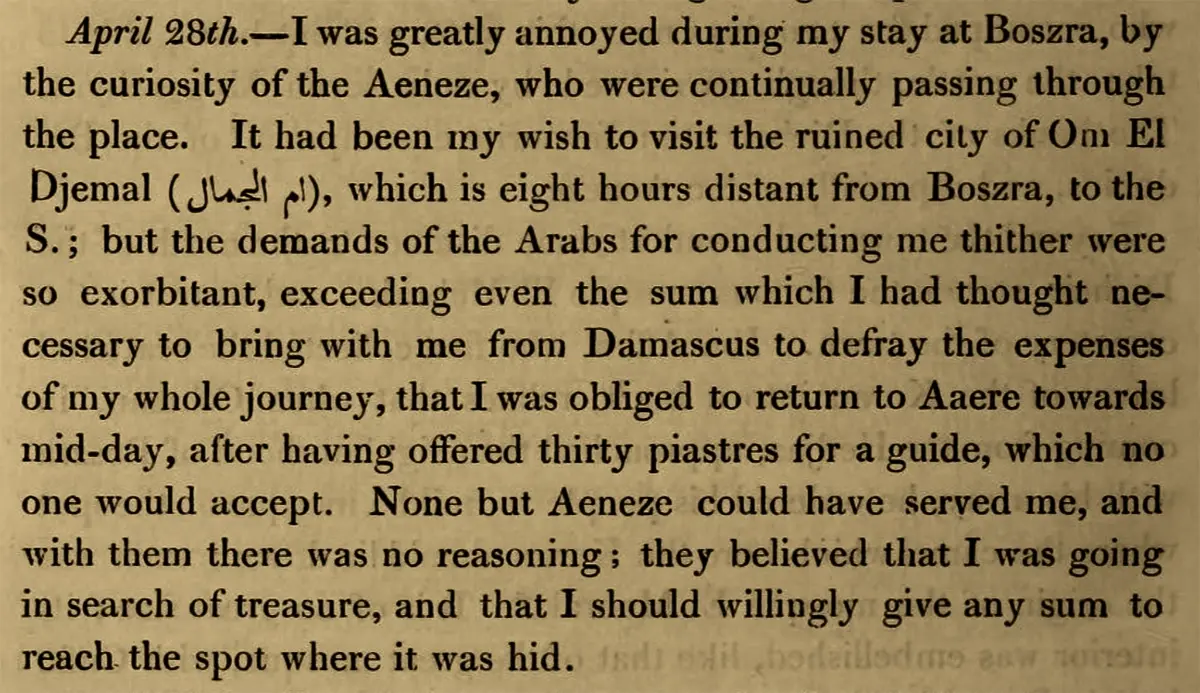

The first outsider to bring Umm Al-Jimal to European attention was Johann Ludwig (John Lewis) Burckhardt, a Swiss traveler working under British patronage and better known today for "rediscovering" Petra in 1812. Disguised as a Muslim trader, Burckhardt spent years crisscrossing the Levant, recording sites and gathering intelligence. Twice he tried to reach Umm Al-Jimal—first in 1810, then again in 1812—but both times he failed.

Why? Local guides demanded outrageous sums to lead him there. They suspected he was seeking hidden treasure and refused to believe that he would pay only for curiosity. Burckhardt recorded his frustration: after offering thirty piastres, he had to turn back, the Bedouin insisting that nothing less than a small fortune would suffice. To the tribes who controlled the plain, Umm Al-Jimal was no harmless curiosity but a place that stirred suspicion and guarded secrets.

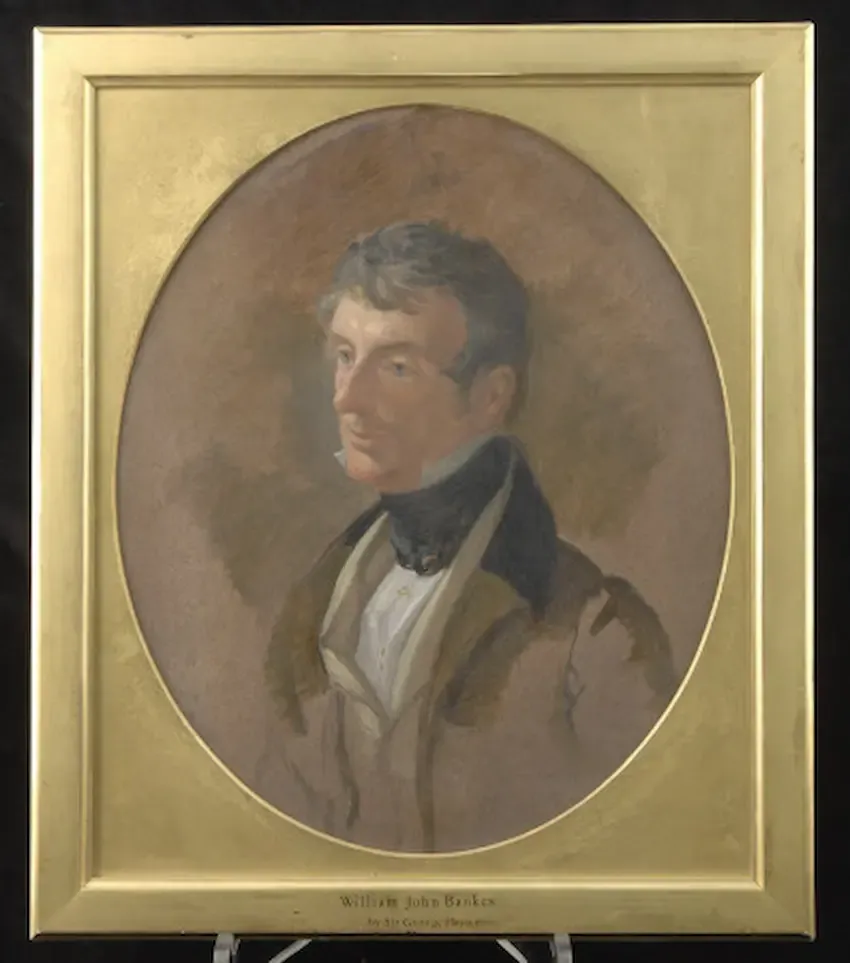

Still, Burckhardt carried news of the site with him. And in Cairo, around 1815–16 after his Petra visit had made him famous, Burckhardt met two young British travelers—James Silk Buckingham and William John Bankes—to whom he spoke of this mysterious black-stone city he had failed to reach. In that moment, the torch of Umm Al-Jimal's story passed to another generation. It's easy to imagine that these two young men envisioned their own future glory if they could accomplish what Burckhardt could not.

Buckingham and Bankes: Companions, Rivals, and a Courtroom Battle

Buckingham and Bankes were very different men. Buckingham, self-taught and ambitious, was a restless traveler who made his living from publishing accounts of his journeys. Bankes was wealthy, scholarly, and eccentric, an antiquarian with deep classical learning and a taste for collecting. For a short time, the two traveled together before reaching the Hauran, accompanied by Giovanni Finati, an Italian adventurer who had converted to Islam and who had accompanied Bankes from Cairo.

But their paths soon diverged. In 1816, Buckingham reached Bosra, where he heard stories of Umm Al-Jimal. He wrote of a ruined city, uninhabited but large, with the remains of a Christian church and many houses. He also noted that the Beni Sakhr tribe of Bedouins used the site as a stronghold for their raids in the region, painting it as a dangerous place even to approach. Yet he never went there himself: his knowledge was second-hand, a tale passed along by locals. These adventurers would briefly meet up again in Damascus—where they shared stories and information gathered on their separate travels—before yet again setting out in different directions.

Bankes, meanwhile, returned to the Hauran two years later, this time without Buckingham or Finati. In 1818, he did what the others had not: he walked among Umm Al-Jimal's ruins. He copied twelve Greek and Latin inscriptions, leaving behind the earliest known Western record of the site. But Bankes never published his findings.

The relationship between the two men dissolved into acrimony. Bankes accused Buckingham of stealing from his notes (possibly during their shared time in Damascus). Buckingham denied it. Their feud ended up in the British courts, where Buckingham sued for libel and, in 1826, won £400 in damages. For Bankes, it was a humiliating defeat. It may be that this loss, and the fear of further controversy, kept Bankes from ever publishing his careful observations. His notes remained hidden in private archives for generations.

Because of this silence, the credit for Umm Al-Jimal's "first discovery" drifted elsewhere. For much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it was thought that the earliest visitor was Cyril Graham in 1857. Only in the 1990s, when Bankes' notebooks were studied and published, did scholars realize that he—not Graham—had been the first Westerner to walk the streets of Umm Al-Jimal.

Graham's Arabian Nights

If Bankes's visit was forgotten, Cyril Graham's was anything but. Traveling through the Hauran in 1857, Graham produced one of the most famous descriptions of Umm Al-Jimal ever written. He spoke of the challenges of reaching the site: bandits on the plain, Druze-Bedouin tensions, and the exorbitant sums demanded for safe passage, which he bargained down from one thousand piastres to four hundred. And then he described what he saw:

This is, perhaps, among the most perfect of the old cities which I saw… so perfect was every street, every house, every room, that I could almost have fancied, as I was wandering alone in this city of the dead—seeing all perfect, and yet not hearing a sound—that I had come upon one of those enchanted places that one reads of in the Arabian Nights, where the population of a whole city had been petrified for a century.

Graham's words captured imaginations. They turned Umm Al-Jimal into an enchanted ruin, a city of silence and mystery, a place belonging as much to fantasy as to history. He also speculated that the ruins might be biblical Beth Gamul, mentioned in Jeremiah 48: a connection now rejected by modern scholarship but long repeated in secondary sources. For more than a century, Graham was remembered as the site's first Western visitor: a reputation he did not actually deserve, but one that his evocative prose ensured.

Merrill's Detailed Observations and Preservation Warning

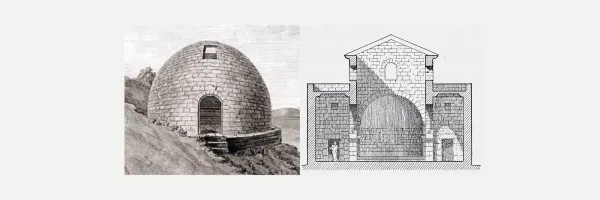

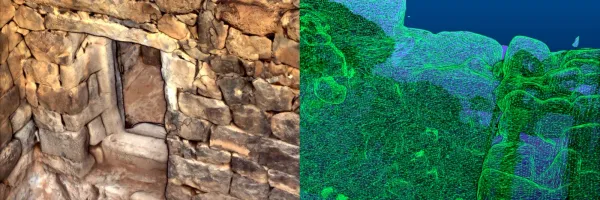

Two decades later, Umm Al-Jimal received another kind of attention. Selah Merrill, an American Congregationalist minister, early archaeologist, and later U.S. consul in Jerusalem, visited the site in 1875. His account offers the most detailed nineteenth-century description of the ruins: he measured parts of the town, described its characteristic multi-storey basalt houses clustered around shared courtyards, noted inscriptions and pottery, and even remarked on the mixture of Roman and Byzantine architectural features. Yet the most striking element of Merrill's account is his growing awareness that the site was in danger.

During his visit, Merrill noticed men dismantling the ruins. Long basalt beams were being pried from the houses and loaded onto camels, carried off to build elsewhere. He worried that inscriptions could be lost forever, carted away one block at a time. "As many as six men were at work while we were there," he wrote, "throwing down the walls and getting the long roof-stones."

This was something new. Where earlier visitors had seen enchanted cities or romantic ruins, Merrill combined careful measurement with concern for preservation. His attention to detail—and his warning about ongoing stone-robbing—mark the first clear step toward an archaeological sensibility: an awareness that ruins could be studied systematically and needed protection. Merrill, in this way, was a bridge between the romantics of the mid-nineteenth century and the scientific archaeologists who would arrive in the twentieth.

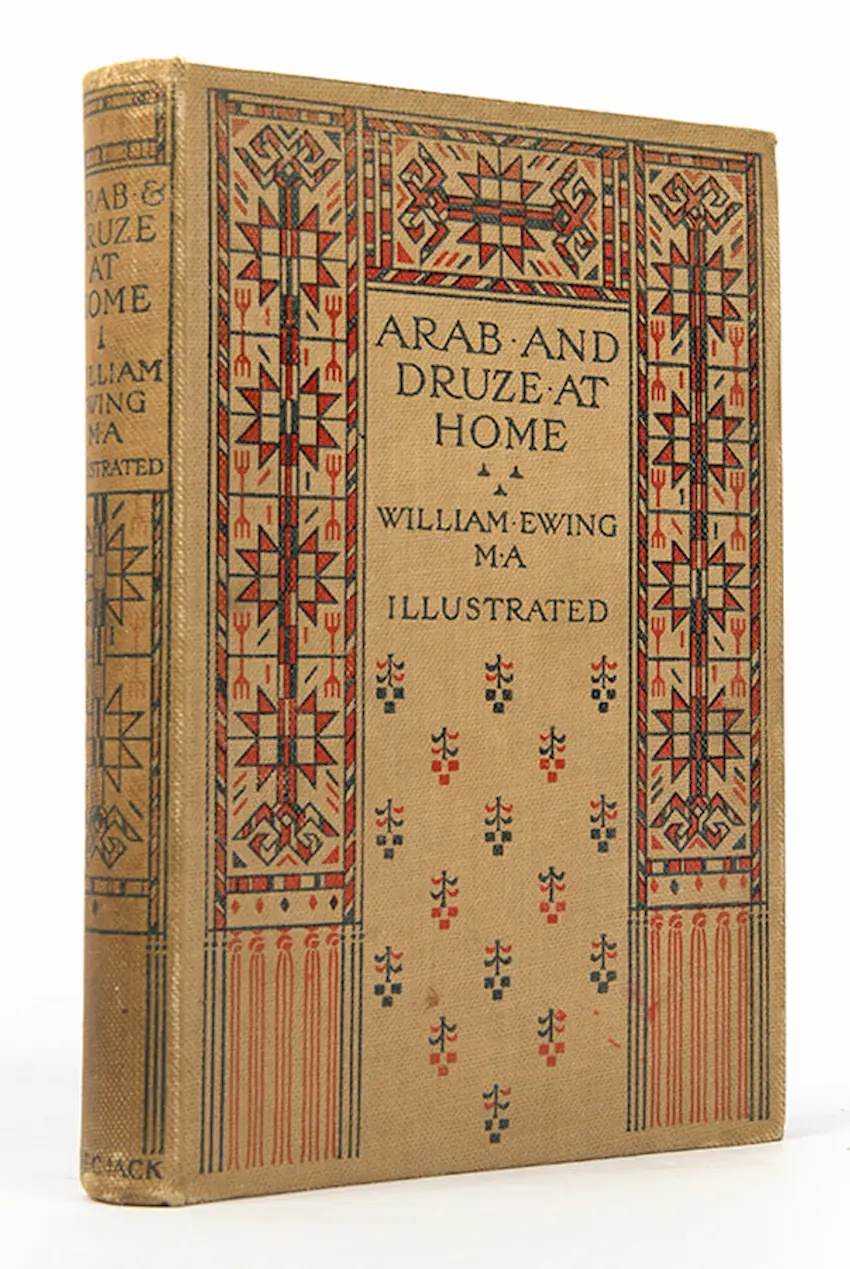

Ewing's Campfire Tale

By the century's end, Umm Al-Jimal had acquired a mythology all its own. In 1895, the American missionary William Ewing wrote down a story he said he heard from Bedouin guides around a campfire: beneath the ruins of Umm Al-Jimal lay a cavern of treasure, hidden by the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) himself, and guarded by forty giant figures, an enormous camel, and a vast serpent whose description reminded Ewing of the biblical Leviathan.

This story reads like folklore and fable, but it is telling. It reveals how Umm Al-Jimal's blackened walls inspired awe, suspicion, and the imagination of both locals and outsiders. It also reflects a pattern that is frustratingly familiar to archaeologists working in the region: ruins across Jordan and Syria are often wrapped in treasure legends, their stones and silence inviting stories of hidden wealth and even supernatural guardians.

From Fantasy to Science

By the dawn of the twentieth century, Umm Al-Jimal had been framed as many things:

- A site too dangerous and suspicious to reach, as in Burckhardt's frustrated attempts.

- A place entangled in the story of personal rivalry and courtroom battles in the travels of Buckingham and Bankes.

- An enchanted city—and an early but mistaken biblical identification (Beth Gamul)—in Graham's haunting description.

- The emergence of real detail and a preservation warning in Merrill's anxious report.

- A treasure-guarded cavern in Ewing's campfire tale.

Each account reveals more about the travelers and their times than about the town itself. What none of them captured was the true significance of Umm Al-Jimal: a lived-in city of farmers, soldiers, traders, and families whose homes and churches still stand.

That more accurate picture began in the early 1900s, when Howard Crosby Butler and the Princeton Expedition arrived with cameras, plane tables, and trained epigraphers. They would replace myth with measurement and romantic tales with systematic study. Their story marks the next stage of Umm Al-Jimal's rediscovery—and the subject of our next post.

Continue reading this "Introduction to Umm Al-Jimal" series:

- Umm Al-Jimal: Mother of Beauty, Mother of Camels

- Umm Al-Jimal: Adventurers, Antiquarians, and Arabian Nights (current page)

- Umm Al-Jimal: Princeton Expedition to UNESCO World Heritage Site

Or download the complete essay (including all 3 parts) as a single document:

Further Reading

Darrell J. Rohl (in press). "Mother of Beauty/Mother of Camels: The Rediscovery of Umm Al-Jimal, 1800–2023."

John Lewis Burckhardt (1822). Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. London.

James Silk Buckingham (1825). Travels Among the Arab Tribes. London.

William John Bankes, notebooks (1818; unpublished, Dorset History Centre Archive D-BKL/H/J/7/5/4).

Julian M.C. Bowsher (1997). "An Early Nineteenth Century Account of Jerash and the Decapolis: the Records of William John Bankes." Levant 29. For Bankes' unpublished papers,

Cyril C. Graham (1858). "Explorations in the Desert East of the Hauran and in the Ancient Land of Bashan." Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London 28.

Selah Merrill (1881). East of the Jordan. London.

William Ewing (1897) "A Journey in the Hauran." Palestine Exploration Quarterly 27. Serialized in four parts: pp. 60–67, 161–184, 281–294, and 355–368.