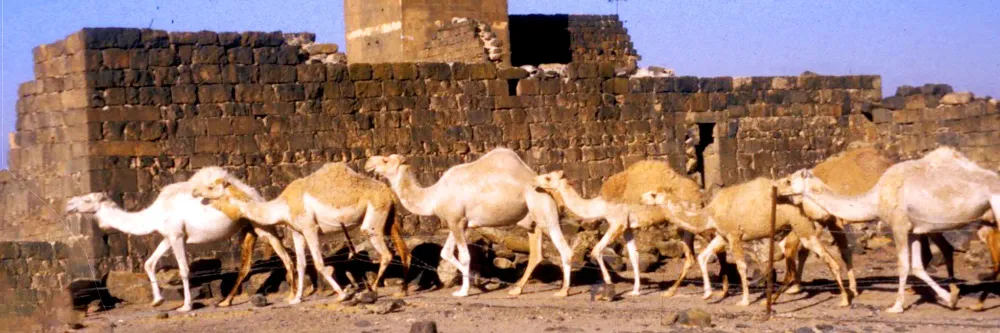

Umm Al-Jimal: Mother of Beauty, Mother of Camels

Far out on Jordan's northeastern plain, black basalt walls rise stark against the sky. From a distance, Umm Al-Jimal doesn't look like a ruin. Its towers, houses, and churches stand so complete that nineteenth-century travelers compared it to an enchanted city from the Arabian Nights—as if its people had been turned to stone and only recently departed. Even today, the impression is uncanny: a desert city frozen in time, waiting for life to return.

But what is this place, and why does it matter?

A Name with Two Meanings

The site's ancient name is lost, and so we know it only by its modern Arabic name: Umm Al-Jimal (ام الجمال). The meaning depends on how you pronounce a single short vowel that is usually unwritten in Arabic texts: it could be the "Mother of Camels" (ام الجِمال, Umm Al-Jimāl), or the "Mother of Beauty" (ام الجَمال, Umm Al-Jamāl), and the difference is subtle when spoken. Both names are evocative, and both appear in older travel accounts, where Western visitors recorded what they thought they heard from local guides.

Even now, the site appears in print as "Umm el-Jimal," "Umm el-Jemal," "Om Edjemal," and similar variations. Part of the problem here is that there are different ways to transliterate Arabic into the Roman/Latin alphabet and different systems and choices have been employed to write the site's name over the past 200+ years. But the official transliteration adopted for Jordan's 2023 World Heritage nomination is "Umm Al-Jimāl," and that is the form preferred today (though I usually simplify by omitting the macron over the final ā, unless I'm writing a very formal and/or official document).

"Mother of Camels" may be the linguistically correct rendering. Yet after several years of working here, I confess a personal preference for the "Mother of Beauty." It captures not only the striking character of the ruins but also the hospitality and resilience of the modern community that calls this place home.

Jordan's Newest World Heritage Site

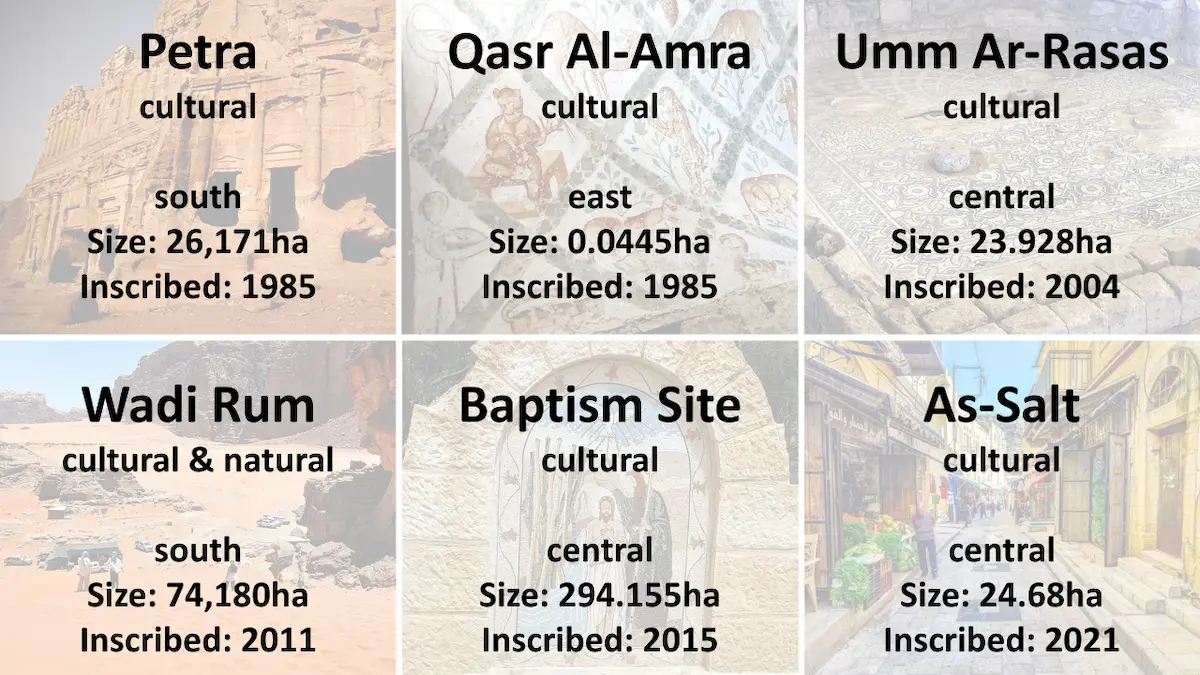

In July 2024, Umm Al-Jimal was officially inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, becoming Jordan's seventh World Heritage Site, and the first in the country's north.

The inscribed property is large: it's about half the size of Jerusalem's Old City, and in Jordan it's nearly double that of Umm Ar-Rasas, and roughly 80% the size of Jerash's visitable archaeological park. For Jordan, Umm Al-Jimal fills an important geographical and historical gap, joining Petra, Qasr Al-Amra, Umm Ar-Rasas, Wadi Rum, Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Al-Maghtas), and As-Salt on Jordan's World Heritage roster.

The inscription recognizes what generations of archaeologists and local residents already knew: that Umm Al-Jimal is among the world's most important and spectacular ancient towns, unmatched for its scale, preservation, and insights into everyday life on the edge of empires.

A Town of Houses, Churches, and More

Unlike Petra with its monumental tombs, or Jerash with its colonnaded avenues and theaters, Umm Al-Jimal tells a different story. Here we find not the trappings of imperial glory but the fabric of domestic life and, remarkably, much of it still stands.

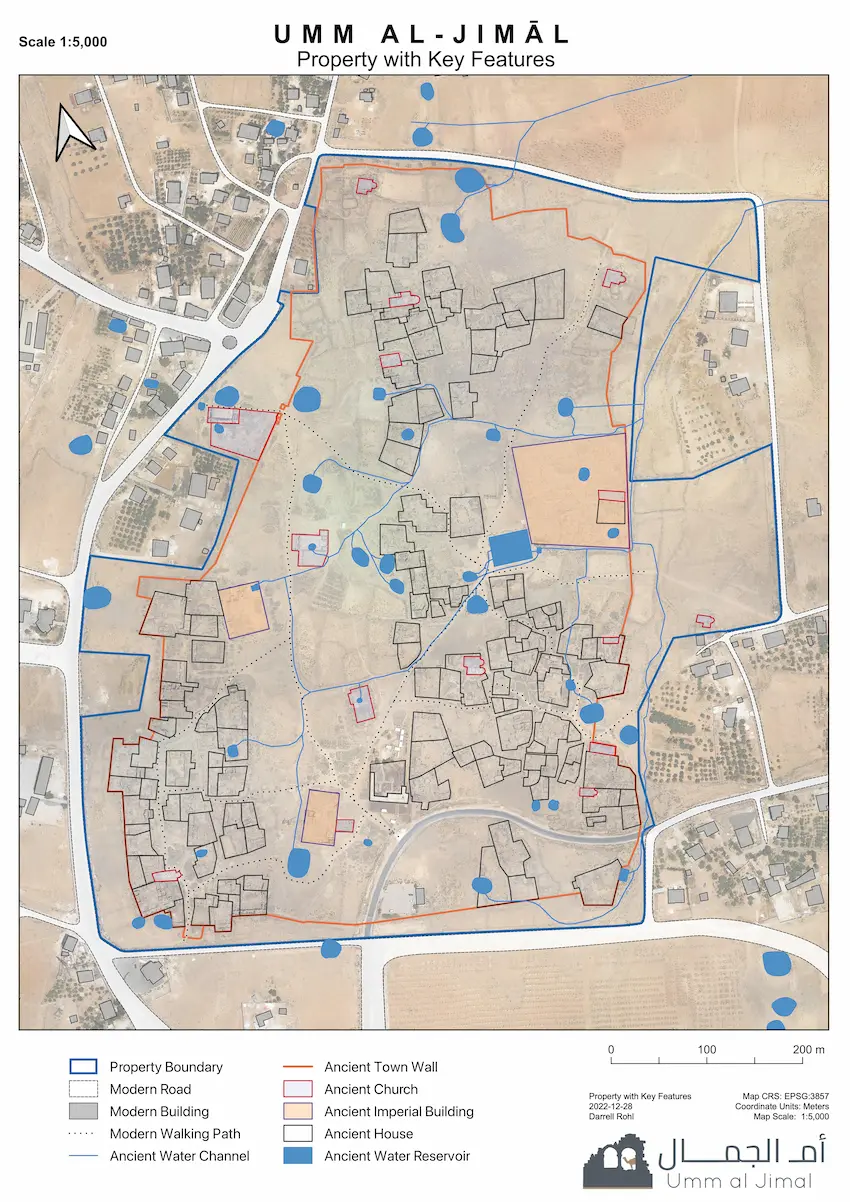

Across its 43-hectare walled town, archaeologists have identified:

- More than 170 ruined buildings, including around 150 houses, many still rising two or three stories high.

- Two Roman forts and an imperial administrative building (the "Praetorium").

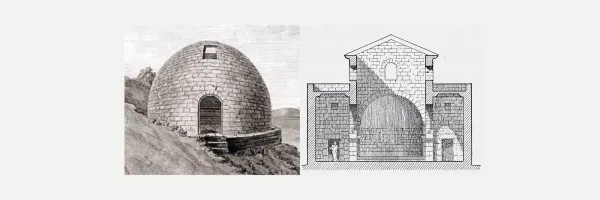

- Sixteen early churches, constructed mainly in the sixth century during the Byzantine Emperor Justinian's empire-wide church-building campaign.

- Three possible mosques, including one adapted from an earlier house.

- A sophisticated water system with more than 30 reservoirs, some of which have been restored, reviving ancient techniques for contemporary desert survival.

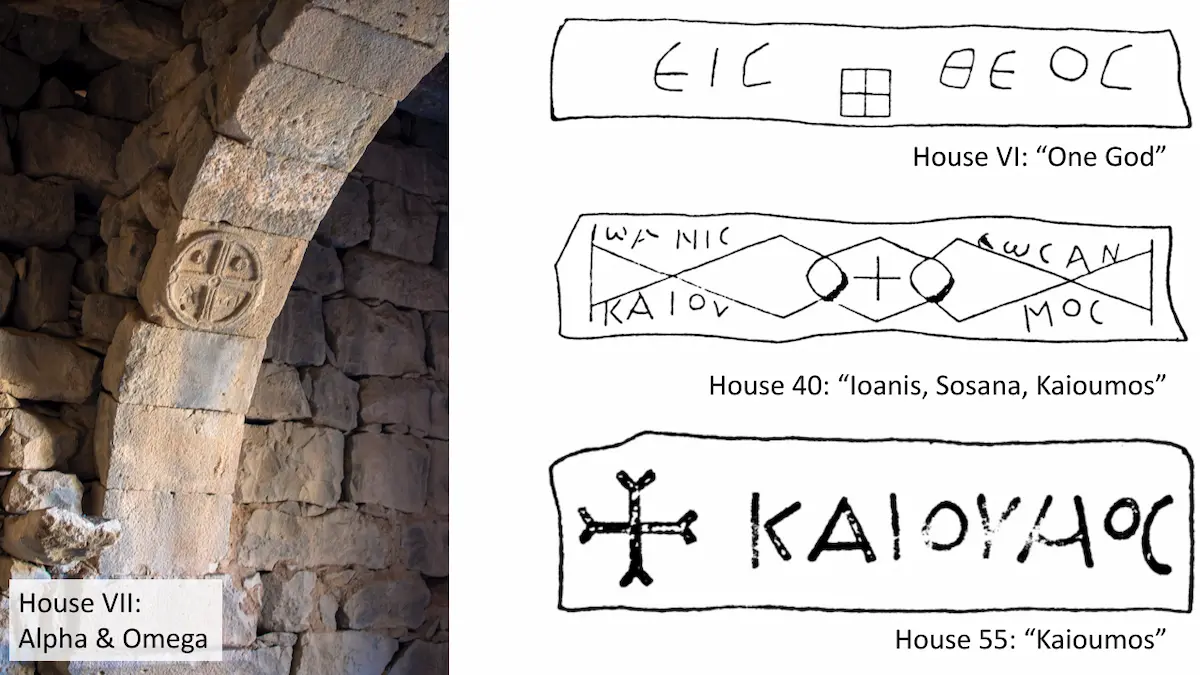

- Over 500 Greek and Latin inscriptions, alongside Nabataean, Safaitic, and Arabic texts—making Umm Al-Jimal the richest epigraphic site in northern Jordan.

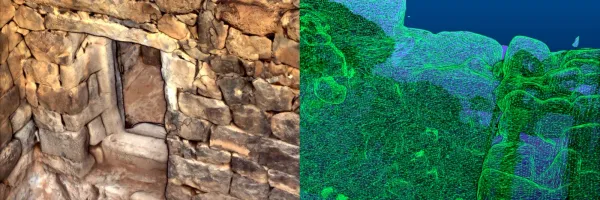

This abundance allows visitors to do something rare: to reconstruct in their minds what the town once looked like, and to imagine the rhythms of ancient daily life. Where Petra dazzles with spectacle, Umm Al-Jimal invites you into kitchens, courtyards, staircases, and doorways: into homes.

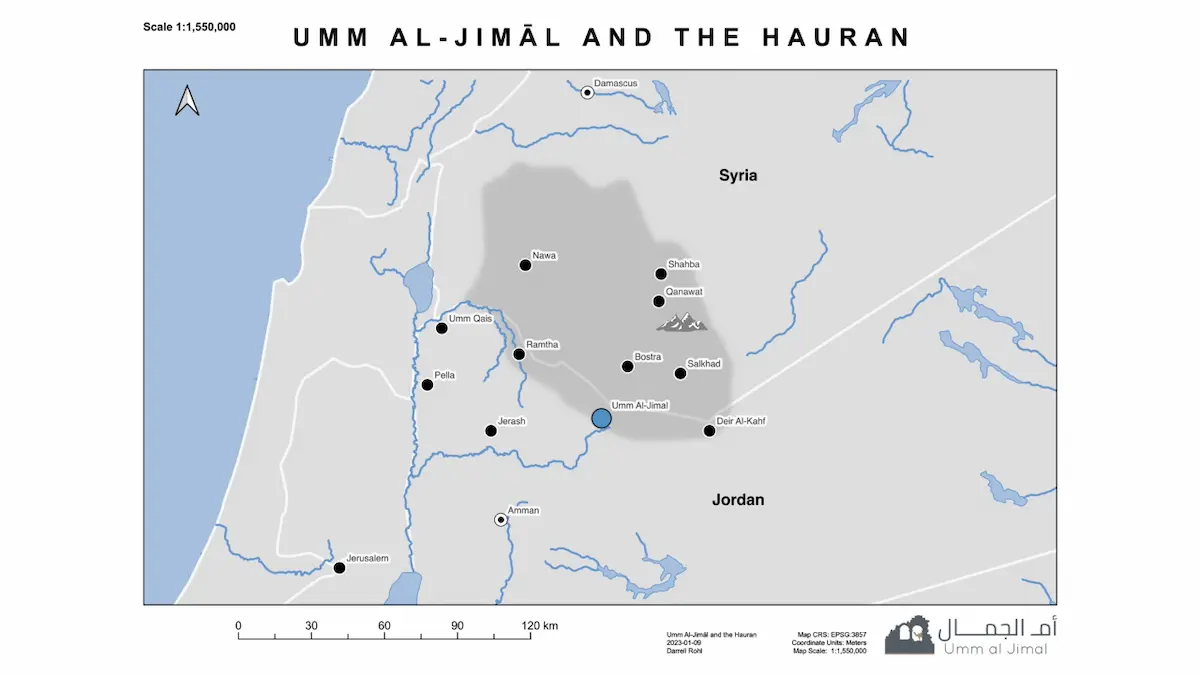

The Hauran: A Black-Basalt Landscape

Umm Al-Jimal's distinctive look is owed to its setting in the Hauran, a vast volcanic plateau formed by eruptions from the Jabal Al-Arab (sometimes called the Jabal Al-Druze) extinct volcano in southern Syria. The region's abundant basalt made for an architectural tradition unlike anywhere else in the Roman world: heavy stone beams instead of timber, cantilevered staircases, corbelled arches, and walls so strong that houses could stand three or even four stories.

Geographically, Umm Al-Jimal sits at the very southern edge of the Hauran, just inside Jordan's borders. This has two important consequences:

- First, the site reflects cultures and communities that transcended modern frontiers. While Umm Al-Jimal is proudly Jordanian today, it also embodies the wider regional identity of the Hauran, straddling the contemporary states of Syria and Jordan.

- Second, its position in Jordan spared it from the devastation of Syria's recent civil war, which tragically destroyed many ancient sites across the border.

This makes Umm Al-Jimal not only the largest but also the most complete surviving Hauranian town.

A Timeline in Stone

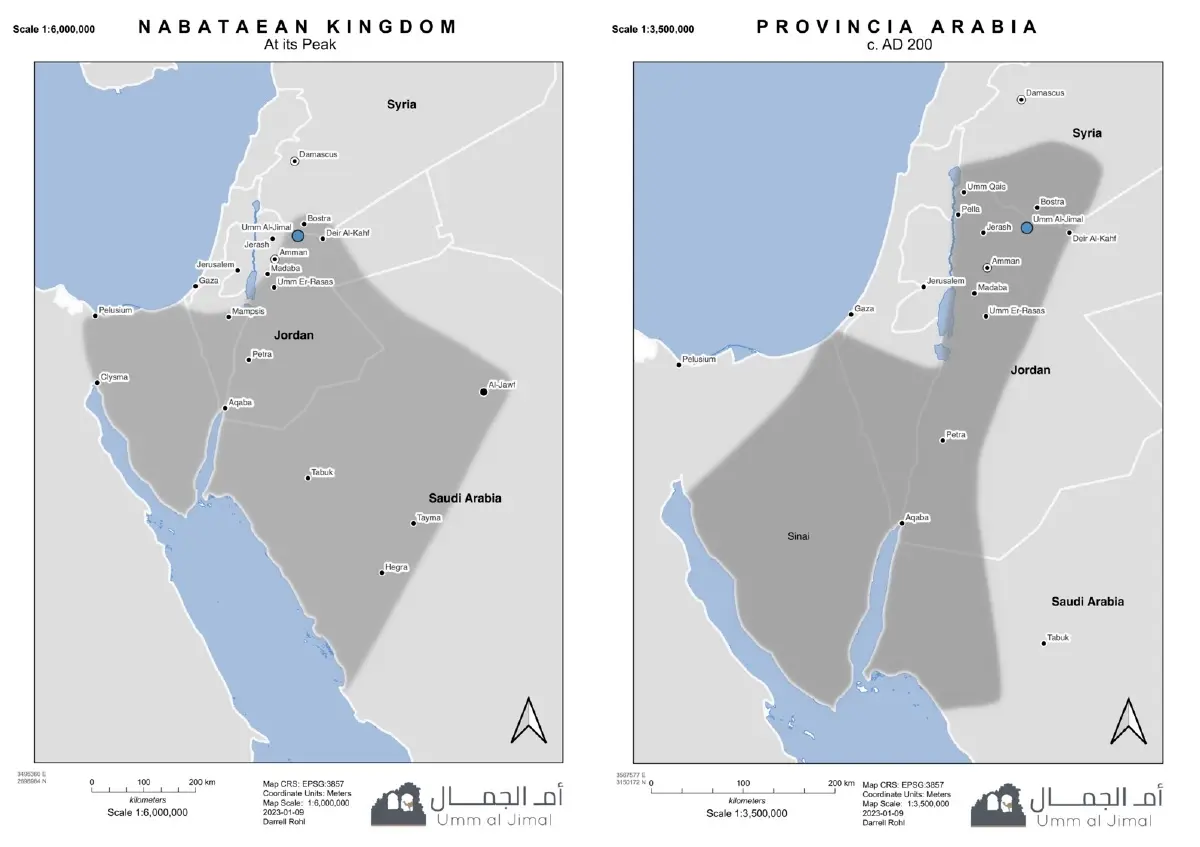

Archaeology shows that Umm Al-Jimal was first settled in the late first century CE by the Nabataeans, whose kingdom is better known for Petra, but had then established a new—or, perhaps, a secondary—capital at nearby Bostra (now called "Bosra," just 23 km away in modern-day Syria).

Its fortunes rose when Rome annexed Nabataea in 106 CE, creating the new province of Arabia, with Bostra as the provincial capital. Proximity to Bostra gave Umm Al-Jimal an outsized role for a rural town. In fact, several of its residents served as council members (bouletes) in Bostra, underlining Umm Al-Jimal's connection to the political life of the province.

The site expanded under Rome, suffered during Queen Zenobia's short-lived Palmyrene rebellion in the late third century, and reached its flourishing peak in the Byzantine sixth century, when most of its surviving churches and houses were built. By the end of the eighth century, as the Abbasid caliphate shifted power east to Baghdad, Umm Al-Jimal was largely abandoned for the next millennium.

Yet the story didn't end there. Bedouin tribes used the ruins seasonally for centuries, Druze families settled here in the early twentieth century, and members of the Bedouin Masa'eid tribe pitched their tents among the ancient walls until the 1970s, when the government enclosed the ruins for protection. Today, the modern village of Umm Al-Jimal encircles the ancient one, and the people of the town remain vital stewards of the heritage at their doorstep.

Faith in Daily Life

If Umm Al-Jimal is extraordinary for its architecture, it is just as remarkable for the ways it reveals the interweaving of faith and everyday life.

Sixteen ancient churches have been documented, many squeezed into domestic neighborhoods. Some were public parish churches, others private family chapels, and still others funerary or possibly monastic in function. Several houses preserve crosses and inscriptions carved above doorways or in arches: simple graffiti-like markings that echo John Chrysostom's fourth-century exhortation to integrate faith into all aspects of life and to "make your house a church."

For scholars, these features offer a window into how religion permeated daily life. For visitors, they provide something more immediate: the sense that you are walking not through monuments for elites, but through the homes, prayers, and memories of ordinary people.

Preservation and Partnership

Over the past fifty years, the Umm Al-Jimal Archaeological Project (UJAP) has documented the town's architecture, inscriptions, cemeteries, and water systems. Under the leadership of the late Bert de Vries and now a new generation of scholars, the project has embraced "community archaeology," working closely with the modern residents of Umm Al-Jimal to ensure that the site's benefits are shared. It is my great privilege and honor to be a part of this new generation, serving as Co-Director and Director of Excavations.

And this community partnership was vital to the UNESCO nomination. Supported by Jordan's Department of Antiquities, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, the Umm Al-Jimal Municipality, and international partners, the nomination succeeded because it combined world-class scholarship with engaged local stewardship.

In 2024, UNESCO and ICOMOS recognized the site's "Outstanding Universal Value," enhancing its protection for future generations.

Why Visit Umm Al-Jimal?

Because nowhere else in Jordan—or the Roman/Byzantine Near East—can you explore an entire town so intact. Walk through its gates, climb its staircases, and step into its courtyards, and you're entering a place that still speaks. Jordan is absolutely worth a visit, for several compelling reasons:

- If you want to marvel at Nabataean artistry, you go to Petra.

- If you want Roman theaters, temples, and colonnades, you go to Jerash.

- If you want dazzling mosaics, you go to Madaba or Umm Ar-Rasas.

- If you want a deeply spiritual experience—to stand where Jesus was baptized and to walk in the footsteps of prophets and pilgrims—you go to the Baptism Site at Bethany Beyond the Jordan.

- But if you want to know how people actually lived—in houses, neighborhoods, and communities—you go to Umm Al-Jimal.

It is, quite simply, the Mother of Beauty.

What's Next?

In the next post: "Adventurers, Antiquarians, and Arabian Nights," learn how Umm Al-Jimal first entered the Western imagination through the eyes (and pens) of nineteenth-century travelers.

Continue reading this 3-part "Introduction to Umm Al-Jimal" series:

- Umm Al-Jimal: Mother of Beauty, Mother of Camels (current page)

- Umm Al-Jimal: Adventurers, Antiquarians, and Arabian Nights

- Umm Al-Jimal: Princeton Expedition to UNESCO World Heritage Site

Or download the complete essay (including all 3 parts) as a single document:

Further Reading

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, E.A. Osinga, J. de Vries Morton, and D.J. Rohl (2023). Umm Al-Jimāl: UNESCO World Heritage Nomination and Site Management Plan. Amman: Department of Antiquities of Jordan.

Bert de Vries (1998). Umm el-Jimal: A Frontier Town and Its Landscape in Northern Jordan. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series.

Elizabeth A. Osinga (2017). The Countryside in Context: Stratigraphic and Ceramic Analysis at Umm el-Jimal and Environs in Northeastern Jordan (1st to 20th Century AD). Doctoral thesis, University of Southampton.

Darrell J. Rohl (2025). "Umm Al-Jimal: Jordan's Newest UNESCO World Heritage Site." ACOR Spring 2025 Lecture.

Darrell J. Rohl (in press). "Mother of Beauty/Mother of Camels: The Rediscovery of Umm Al-Jimāl, 1800–2023."

N.T. Bader (2009). Inscriptions grecques et latines de la Syrie XXI: Inscriptions de la Jordanie, tome 5. Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient.