Umm Al-Jimal: Princeton Expedition to UNESCO World Heritage Site

This is Part 3 of a 3-part series of posts introducing the site of Umm Al-Jimal, Jordan (see Part 1), the current focus of my work as a scholar of archaeology and heritage. Having traced Umm Al-Jimal's emergence from legend into the pages of nineteenth-century travel (see Part 2), we now follow its transformation into a subject of serious archaeological study. From Princeton's early surveys and Corbett's first excavation to Bert de Vries' establishment of the long-term Umm Al-Jimal Archaeological Project, and UNESCO recognition in 2024, this final installment shows how careful measurement, community partnership, and persistence turned a "petrified city" into a living World Heritage Site.

Continue reading here, or download the complete essay (all 3 parts) as a single document:

Part 3: Princeton Expedition to UNESCO World Heritage Site

When nineteenth-century travelers wrote about Umm Al-Jimal, they conjured an enchanted city of basalt; silent, mysterious, biblical, legendary, and perhaps even cursed. By the dawn of the twentieth century, however, the age of romantic travel writing was giving way to something new. Cameras complemented sketchbooks, measuring tapes and theodolites replaced rifles, and questions of treasure and legend yielded to those of architecture, chronology, and preservation.

The story of Umm Al-Jimal's modern archaeology begins here: with surveyors and epigraphers from Princeton University who traded campfire tales for contour lines, and ends—at least for now—with its inscription as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2024.

The Princeton Expedition

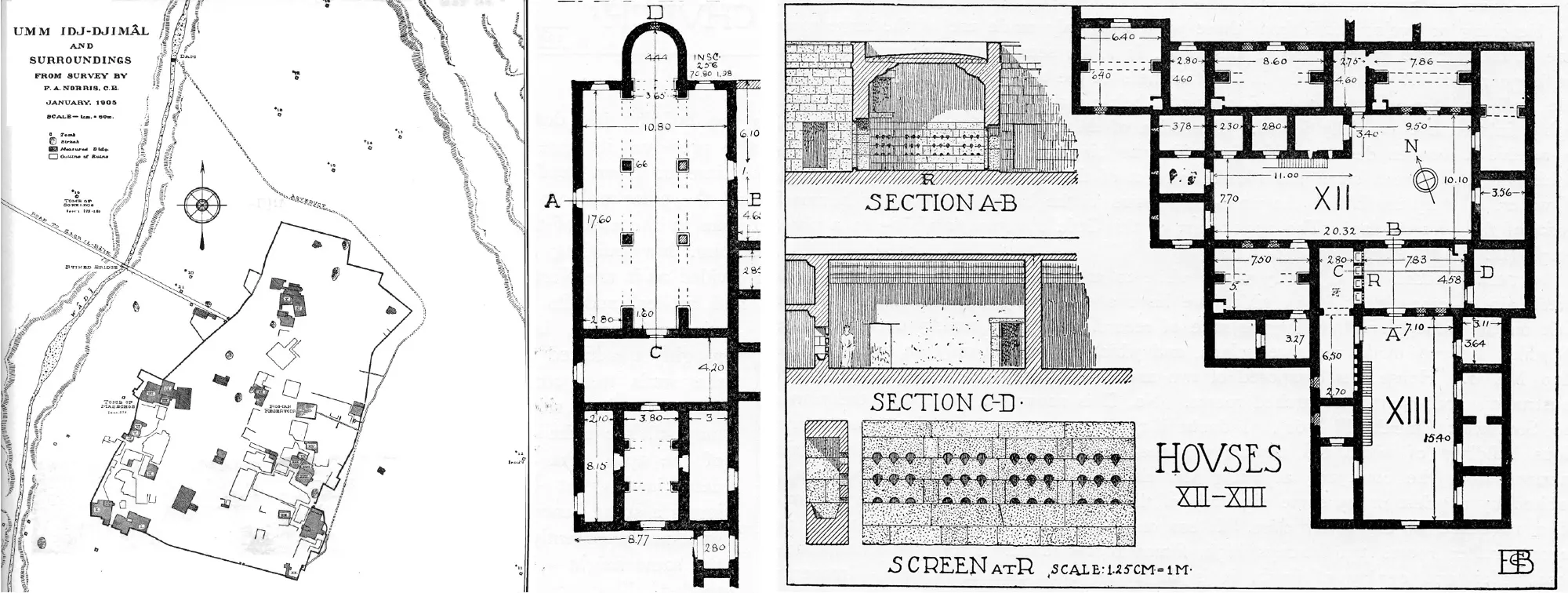

In 1905, Howard Crosby Butler and a team from Princeton University set out to document the antiquities of southern Syria and northern Jordan. Their Princeton Expedition to Syria visited Umm Al-Jimal twice, in 1905 and 1909, as part of a sweeping survey of the Hauran.

Butler opened his report with a passage that could easily have been written by Cyril Graham half a century earlier:

Far out in the desert, in the midst of a rolling plain, beside the dry bed of an ancient stream, there is a deserted city… The walls of the ancient deserted city, its half-ruined gates, the towers and arches of its churches, the two and three-storey walls of its mansions, all of basalt, rise black and forbidding from the grey of the plain. Many of the buildings have fallen in ruins, but many others preserve their ancient form in such wonderful completeness, that, to the traveller approaching them from across the plain… the deserted ruin appears like a living city, all of black, rising from a grey-white sea.

The tone is both poetic and precise—a bridge between the enchanted city of the nineteenth-century imagination and the measured plans of modern archaeology.

At Umm Al-Jimal they recorded:

- The first measured plan of the town—twenty houses, several churches, and the most visible Roman and Byzantine structures.

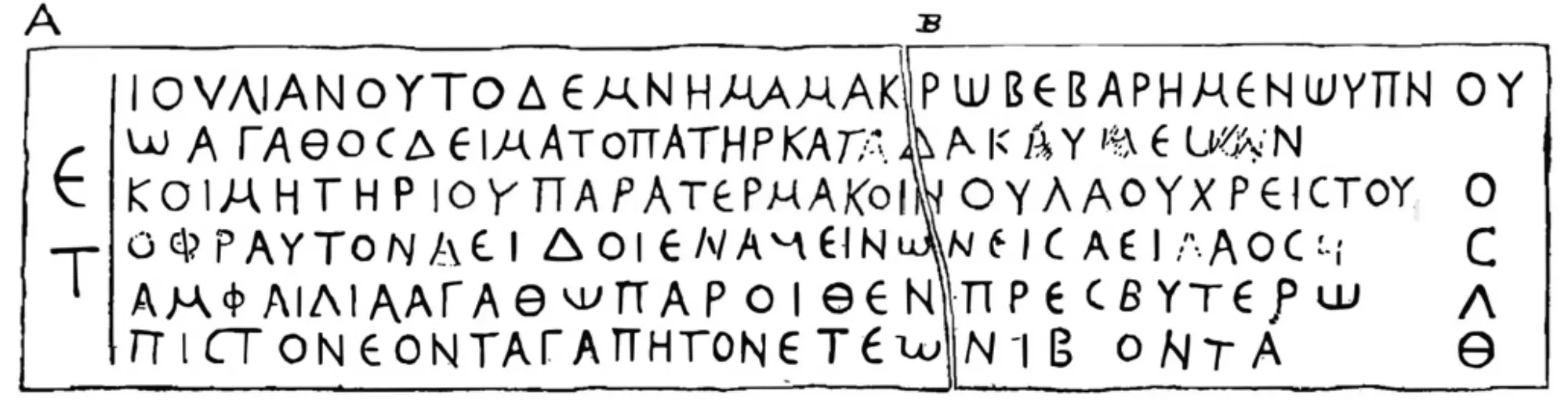

- Hundreds of Greek, Latin, and Semitic inscriptions, including the now-famous Julianos inscription.

- A photographic archive that remains an irreplaceable record of the site before modern disturbance including an earthquake in the 1920s.

Butler's work was groundbreaking: a deliberate attempt to map rather than romanticize. His plans turned the "black city" into a dataset: an object of study, not legend. Yet it was also selective. Butler focused on major monuments and inscriptions, largely ignoring ordinary domestic architecture and stratigraphy. His aim was to document the site's most significant features, not to dig or provide a comprehensive account.

Even so, the Princeton Expedition marked a decisive turn from myth to measurement. It anchored Umm Al-Jimal in academic geography and made it visible to the wider archaeological world.

Gertrude Bell and the Early Twentieth Century

Among the others who came in this period was Gertrude Bell, who visited in 1905 on her remarkable journeys through the Levant. Her photographs, now preserved in the Newcastle University archive, show arches, towers, and staircases that have since collapsed—quietly capturing details that no longer survive. As she recorded her first glimpse of the site, she expressed amazement at "its black towers and walls standing so prominently in the desert that it was hard to believe it had been abandoned for over thirteen centuries."

Bell's visit, and others like it, kept Umm Al-Jimal in scholarly awareness during the decades after Princeton, but it would be decades before additional fieldwork was done. Political instability, limited resources, and shifting archaeological priorities meant that the site once again slipped into silence—waiting nearly half a century for the next major intervention.

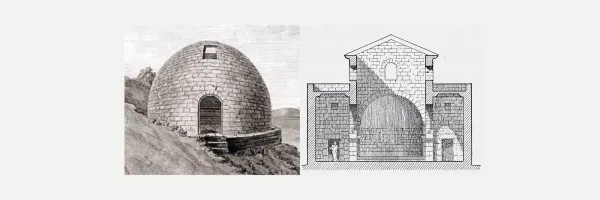

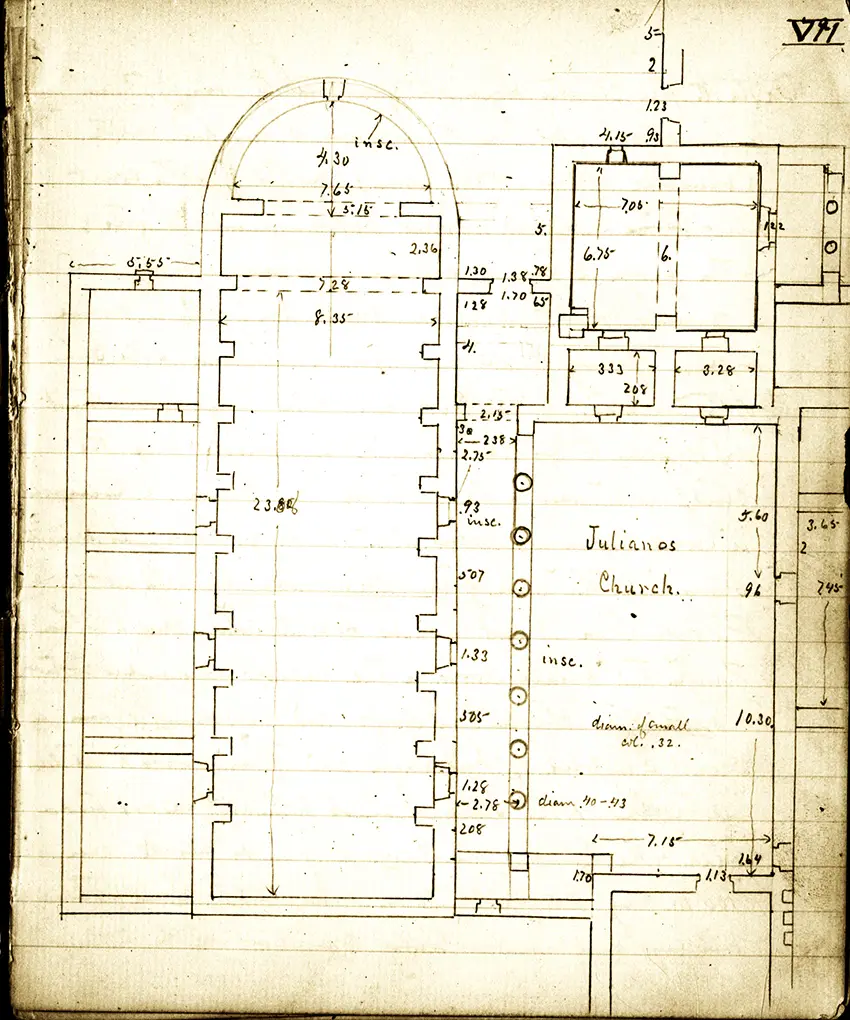

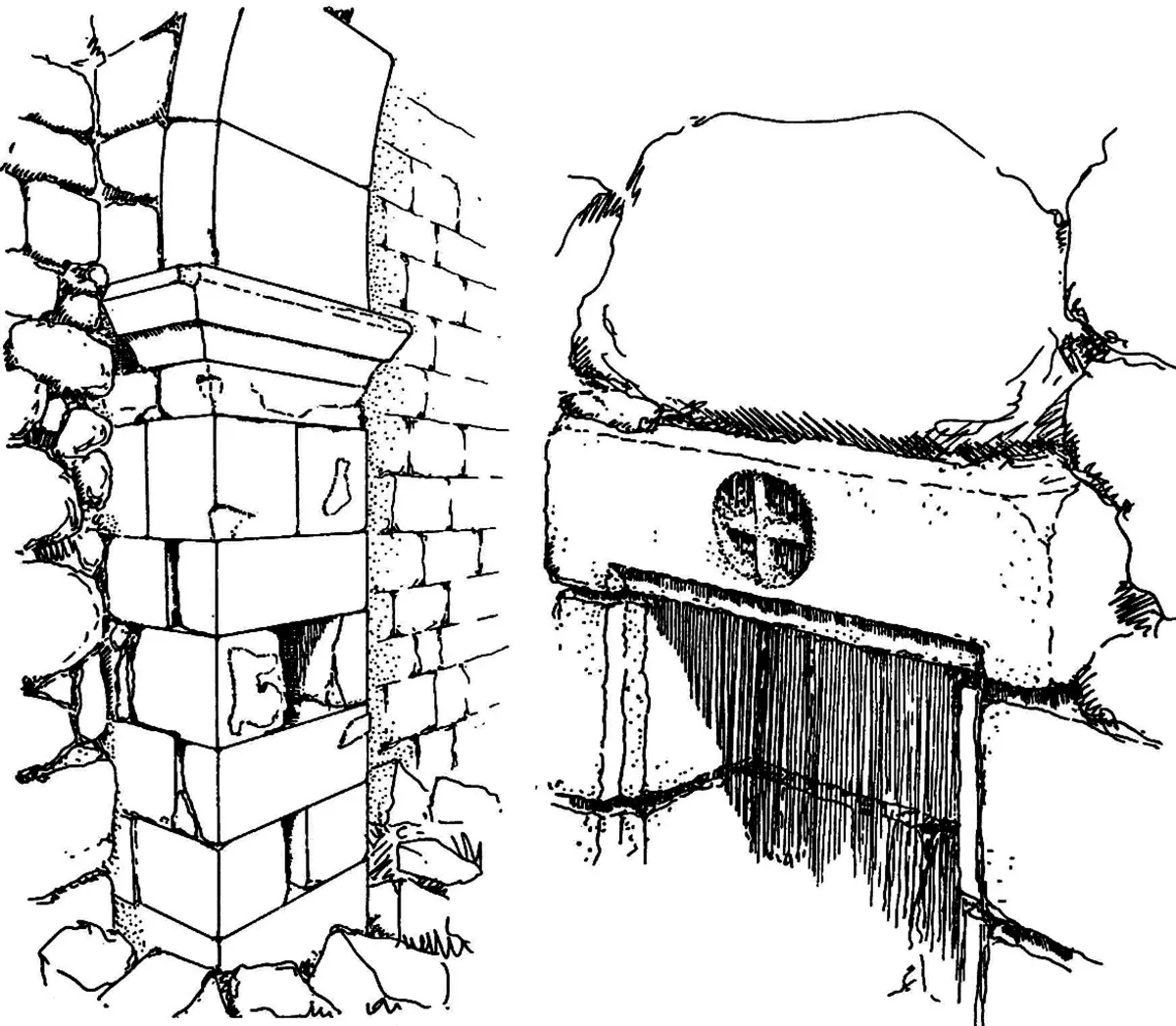

Corbett and Reynolds: Excavating the Julianos Church

That silence ended in the mid-1950s, when C. Corbett and P. A. Reynolds undertook the first planned, stratigraphically recorded archaeological excavation ever carried out at Umm Al-Jimal. Their focus was the Julianos Church, a hall church near the town's northwest corner that had drawn attention because of an inscription discovered by Butler's team half a century earlier.

That Julianos inscription, dated 344 CE (year 239 in the era of Bostra), had led some scholars to proclaim Umm Al-Jimal's Julianos Church "the earliest church in the world with a dated inscription." The claim was carefully phrased: it did not intend to suggest that the church itself was the earliest ever built, only that of all known ancient churches, none possessed an inscription with an earlier date.

Corbett's careful excavation challenged this interpretation. His team documented clear evidence that the inscription was not found in situ, but had been reused in the church’s masonry. Stratigraphic relationships and associated pottery pointed instead to a later construction date, probably in the early part or middle of the fifth century.

Corbett concluded that the famous inscription was almost certainly a reused tombstone, not a building dedication, and that it could not be used to directly date the church. The revelation was significant: it corrected a cherished assumption and replaced speculative dating with stratigraphic reasoning.

Unfortunately, Princeton's influential publications had already entrenched the 344 date in the broader literature. Even today, occasional articles still repeat it. But among specialists more familiar with the site's bibliography, Corbett's correction has stood firm for more than seventy years—a testament to how new evidence can overturn even the most confident claims (but also how difficult it can be to overcome entrenched interpretations!).

Beyond the debate over dates, Corbett and Reynolds' work was a milestone in method. Their excavation introduced modern archaeological technique to Umm Al-Jimal—grids, stratigraphic recording, and attention to material context—bridging the gap between early architectural survey and the scientific programs that would follow.

The Umm al-Jimal Archaeological Project

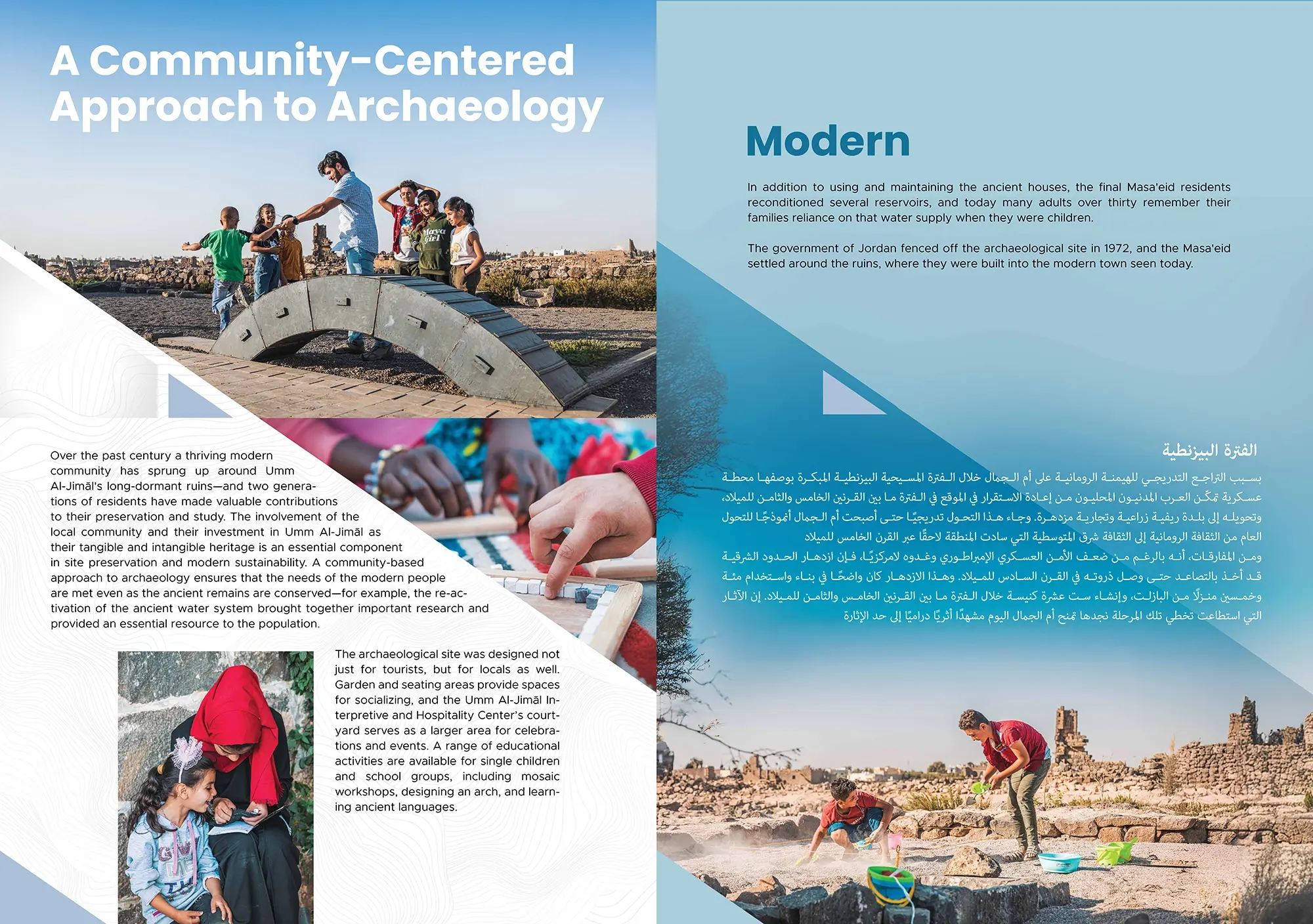

The next great chapter opened in 1972, when Bert de Vries of Calvin University (then "Calvin College") founded the Umm Al-Jimal Archaeological Project (UJAP). De Vries built on Princeton's foundations but brought an entirely new vision: long-term, interdisciplinary, and deeply engaged with the living community.

Over the past five decades, UJAP has (among other accomplishments not noted here):

- Conducted detailed architectural and topographical surveys, identifying over 170 buildings.

- Excavated houses, churches, reservoirs, and towers, revealing the texture of everyday life in Late Antiquity.

- Catalogued hundreds of inscriptions and artifacts, reconstructing patterns of trade and faith.

- Developed heritage management plans and visitor facilities that serve both scholarship and tourism.

De Vries emphasized what he called "the archaeology of the ordinary"—the study of domestic architecture and daily life. His approach made Umm al-Jimal a case study in how provincial towns flourished on the margins of empires.

Equally important was the project's partnership with the modern town. Local residents were trained and employed as excavators, conservators, and guides; their voices shaped interpretation and UJAP has sponsored and supported several local community members through related graduate research. This community-based archaeology has since become a model for other heritage projects in Jordan.

I joined the Umm Al-Jimal Archaeological Project in 2018 and have been Co-Director, along with my colleagues Dr. Elizabeth Osinga and Jenna de Vries Morton, since Bert's unexpected passing in March 2021.

From Research to Recognition

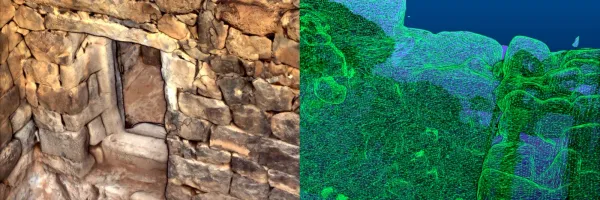

By the early twenty-first century, Umm Al-Jimal was no longer a "lost city" but a vibrant example of integrated heritage practice. Digital documentation, 3-D LiDAR scanning, and GIS mapping—much of it developed under recent research programs—are turning the site into one of the best-recorded ancient towns in the Middle East.

These efforts, together with decades of collaboration among the Department of Antiquities, the Umm Al-Jimal Municipality, and international partners, culminated in July 2024, when Umm Al-Jimal was officially inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It became Jordan's seventh site on the list—and the first in the country's north—recognized for its Outstanding Universal Value as the best-preserved Late Antique town in the basalt Hauran and for its ongoing role as a living community.

Where Burckhardt once failed to reach a city of rumor and danger, the people of Umm Al-Jimal now welcomed the world to a city of knowledge and pride.

Conclusion: The Long (and continuing) Rediscovery

Across two centuries, Umm Al-Jimal's story traces the evolution of archaeology itself:

- In the early 1800s, Burckhardt, Buckingham, and Bankes pursued rumor through risk.

- In the later nineteenth century, Graham and Ewing romanticized and mythologized; Merrill sought out detail and sowed the seeds of preservation concerns.

- Butler's Princeton team turned observation into survey and gave us the first detailed documentation.

- Corbett and Reynolds brought excavation and correction.

- De Vries and the UJAP team he built have greatly expanded knowledge and made archaeology collaborative and community-based.

- UNESCO sealed recognition that Umm Al-Jimal's past and present are inseparable and worth protecting for generations to come.

What began as a "petrified city" has become a living heritage shared by scholars, residents, and visitors alike—a testament to endurance, rediscovery, and the quiet persistence of the past.

This concludes our introductory series but there's much more to be said about Umm Al-Jimal and its ability to teach us about the human past and why it remains relevant in the twenty-first century. I'll continue to post about the site's archaeology and heritage value here, but I hope that this series has given sufficient background to this place that has so thoroughly captured my heart.

You can now download the complete essay (all 3 parts) as a single document:

Further Reading

Howard Crosby Butler (1913–1920). Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expeditions to Syria. Princeton University Press. See also the American and Princeton Expeditions to Syria archive at Princeton University's Visual Resources Collection online.

Gertrude Bell (1907). Syria: The Desert and the Sown. London. See also the Gertrude Bell Archive, Newcastle University Library Digital Collection.

C. Corbett and P. A. Reynolds (1957). "Investigations at 'Julianos' Church' at Umm-el-Jemal." Papers of the British School at Rome 25.

Bert de Vries (1998). Umm el-Jimal: A Frontier Town and Its Landscape in Northern Jordan. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 26.

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, E. A. Osinga, J. de Vries Morton, and D. J. Rohl (2023). Umm Al-Jimal: UNESCO World Heritage Nomination and Site Management Plan. Department of Antiquities of Jordan.

UNESCO (2024) "Umm Al-Jimāl." UNESCO World Heritage List. Paris.